If Egyptologists studied only massive stone monuments, gleaming golden sarcophagi, and brightly painted tomb walls, they would understand ancient Egypt as an almost exclusively masculine world. Most of the pyramids and temples were built to glorify male pharaohs and most of the sumptuously decorated tombs that archaeologists have unearthed belonged to men. “There’s a huge gender gap and a bias toward men in the archaeological record,” says Egyptologist Ines Köhler of Humboldt University. “But people had children, so there must have been at least some women.” Some of these unseen women may be hiding in plain sight on less conspicuous artifacts, such as a 19-inch-tall painted limestone stela on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

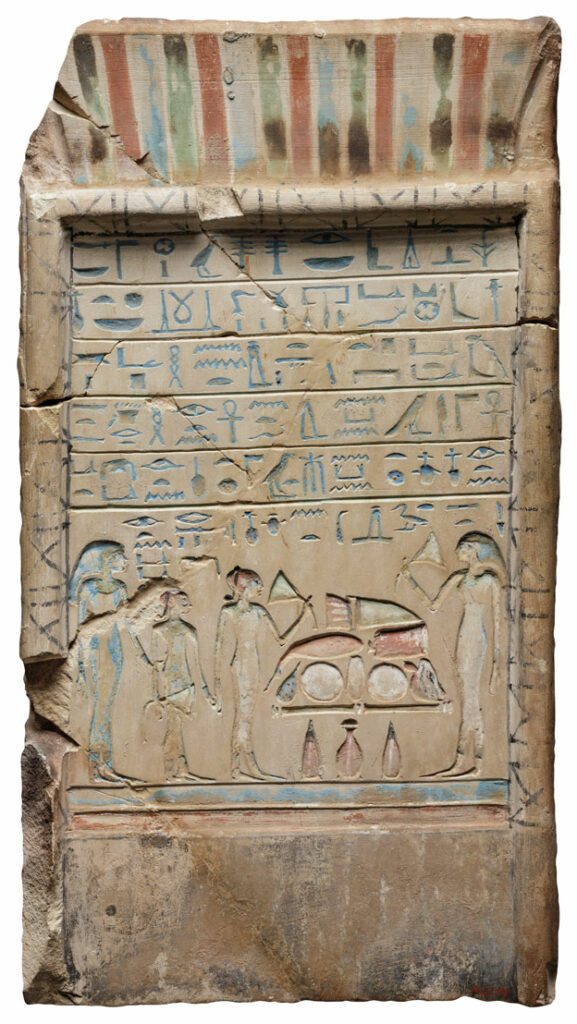

Unearthed by a team from the museum during the 1930s in a prominently located shaft tomb in the necropolis at Thebes, the stela dates to the later part of the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.). Köhler and her fellow Humboldt University Egyptologist Eva-Maria Engel recently reexamined the stela and translated its hieroglyphic inscription. It depicts two adult women and two young girls, possibly sisters, identified by their personal names, which appear above their heads. They stand next to an offering table topped with meat, vegetables, fruit, and bread, under which sit vessels filled with beverages. These four are not, however, the only women mentioned on the stela, as there are nine female names in total. Köhler and Engel have concluded that some of the women belonged to four generations of a single family, including a grandmother, mother, and her niece and daughters. Scholars originally surmised that the stela had fallen into a man’s tomb by accident. “Men’s stelas are never described as falling into shafts by accident. We still say it’s a man’s tomb,” says Engel. “Why can’t this tomb have belonged to a woman or to several women?”

Egyptian stelas identifying extended families of multiple generations are common, but Köhler says that examples including only women are very rare. And, although at least some of the women were blood relatives, she and Engel believe they may also have been linked by a shared profession connected to women’s health, childbirth, and childcare. “Most female professions in ancient Egypt don’t have titles,” Engel says. There are exceptions, such as chantress and priestess, but, she explains, other roles are less frequently attested and therefore difficult to identify. Köhler suggests that women would pass on information about midwifery, child-rearing, and mothers’ and children’s illnesses and health, creating a network of untitled professionals. “Maybe the women on the stela were really close because they all did the same thing and shared their accumulated knowledge,” she says.

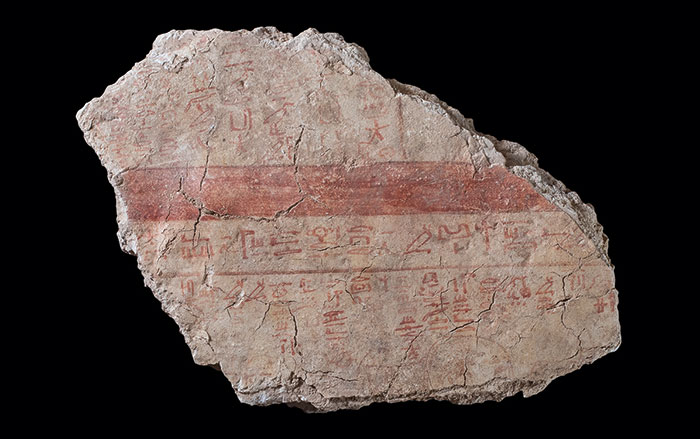

Köhler and Engel’s identification of the tomb as belonging to a woman or women engaged in women’s and children’s care is bolstered by the discovery in the shaft of a birth tusk, made of hippopotamus ivory, also dating to the late Middle Kingdom. The object is carved with an image of a fox head with lotus blossoms between its ears and a row of figures including a knife-wielding jackal, a frog, a crocodile, and a griffin. There are many examples of birth tusks, which are sometimes called magic wands, but Köhler explains that since most came to museums by way of the art market, it’s usually impossible to establish their original context. Nevertheless, based on the images found on these artifacts—protective symbols, demons, animals, and sometimes particular deities or even an inscription related to the safety of a mother and child—it seems clear that they were associated with birth and the protection of pre- and postpartum mothers and children, and with what Köhler and Engel call a more feminine setting. “There are medical papyri that say a lot about women’s health, and especially about contraception, menstruation, and maybe even abortion, but not about how to deal with birth, midwifery, breastfeeding, or children’s care,” Köhler says. “Who do you ask what to do when your baby won’t stop crying? This type of knowledge is transmitted orally, and these women can be somewhat invisible in the archaeological record.” No doubt there are many more subtle traces of women’s lives in the Egyptological record that are waiting to be found by those who know to look for them.