On a sweltering day in 1862 at the foot of the Tuxtla Mountains in the Mexican state of Veracruz, a farmworker was clearing a cornfield when he hit something hard and smooth lodged in the earth. He thought it was the rounded base of an iron cauldron buried upside down, and, it being the 1860s, he reported the find to the owner of the hacienda where he worked. The farmworker’s boss told him to dig up the cauldron immediately and bring it to him. As the farmworker labored to uncover the object, he realized he had found not a large iron bowl, but a gargantuan stone sculpture with a pair of glaring eyes, a broad nose, and a downturned mouth. What had appeared to be the base of a cauldron was actually the top of a helmet worn by the glowering figure. What the farmworker had unearthed was a colossal Olmec head, one of the first clues to the existence of that ancient culture.

Over the next century and a half, archaeologists would uncover many more of these heads along the Mexican Gulf Coast and discover the ancient cities where they were carved. The site of that first fateful discovery became known as Tres Zapotes, after a type of fruit tree common in the area. Along with the sites of San Lorenzo and La Venta, Tres Zapotes was one of the great capitals of the Olmec culture, which emerged by 1200 B.C. as one of the first societies in Mesoamerica organized into a complex social and political hierarchy.

The key to the Olmecs’ rise appears to have been a strong, centralized monarchy. The colossal heads, each one depicting a particular individual, are likely portraits of the Olmec kings who ruled from ornate palaces at San Lorenzo and La Venta. Even though Tres Zapotes yielded the earliest evidence for Olmec kingship, 20 years of survey and excavations there suggest that, at its height, the city adopted a very different form of government, one in which power was shared among multiple factions. Further, while other Olmec capitals lasted between 300 and 500 years, Tres Zapotes managed to survive for nearly two millennia. The city, therefore, may have weathered intense cultural and political shifts not by doubling down on traditional Olmec monarchy, but by distributing power among several groups that learned to work together. According to University of Kentucky archaeologist Christopher Pool, who has spent his career excavating the city, that cooperative rule may have helped Tres Zapotes endure for centuries after the rest of Olmec society collapsed.

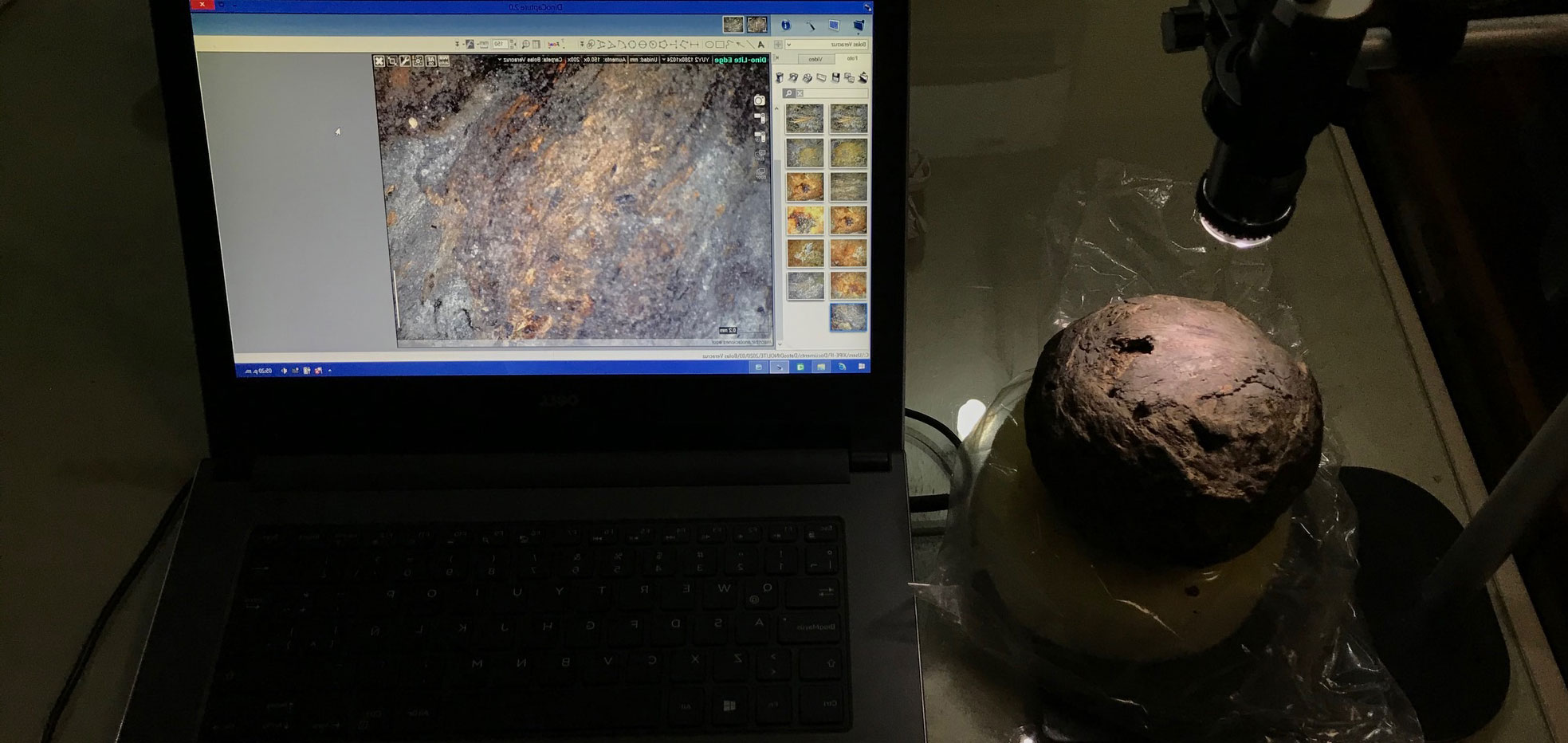

When Pool arrived at Tres Zapotes in 1996, he was the first archaeologist in over 40 years to take a serious interest in the site. Tres Zapotes had been recognized as an important Olmec center since shortly after the discovery of the colossal head, and in the decades to follow it had yielded a plethora of intricate figurines and stone monuments, including another colossal head. But important details of the site’s history remained unknown, including its size and how long it had been occupied. Pool set out to map the full extent of the ancient city, survey the ceramics he found scattered across the ground, and excavate the most compelling areas.

Battling dense fields of sugarcane, swarms of mosquitoes, and the occasional poisonous snake, Pool painstakingly reconstructed the layout of Tres Zapotes and how it had changed over time, and began to be able to compare it to the other great Olmec capitals. Between 1000 and 400 B.C., in a period called the Middle Formative, Tres Zapotes was a minor regional center covering around 200 acres. At the time, La Venta and its all-powerful king dominated the Olmec heartland. Like its predecessor San Lorenzo, which flourished between 1200 and 900 B.C., La Venta was organized around a single dominant plaza featuring administrative buildings, elaborate monuments, and elite residences. The kings whose likenesses are memorialized by the colossal heads lived in palaces that brimmed with precious exotic goods, such as greenstone imported from Guatemala and polished iron-ore mirrors from Oaxaca and Chiapas. Their subjects, meanwhile, lived in modest households arrayed around the central plaza. The concentration of wealth and power in the center of the city, as well as art that glorified individual rulers, suggests that “the Olmecs had a cult of the ruler,” says Barbara Stark, an archaeologist at Arizona State University who works on the Gulf Coast of Mexico.

During La Venta’s height, Tres Zapotes operated under a similar model. As the nineteenth-century farmworker was the first to discover, it too had rulers represented by colossal stone heads. Despite being a relatively small city, it was also organized around a dominant central plaza. Elite burials discovered by Pool were filled with grave goods such as ceramic goblets and jade beads fashioned into jewelry. Another burial Pool uncovered contained no objects at all, hinting at possible social or class differences within the city’s population at that time. While Pool doubts that Tres Zapotes was under La Venta’s direct control during the Middle Formative period, it was clearly part of the same cultural and political tradition.

Around 400 B.C., La Venta abruptly collapsed. Archaeologists still aren’t sure why, but they have found evidence that traders stopped bringing luxury goods into the city. “A lot of [the Olmec rulers’] authority was supported by great displays of exotic wealth,” Pool says. When access to those goods was cut off, the resulting loss of status could have destabilized the monarchy’s control. Evidence shows that the city was quickly abandoned, and, absent any mass graves or other signs of violence, it seems that people likely poured out of the once-grand capital, looking for a new place to call home.

Researchers believe that it’s possible many of them moved to Tres Zapotes, 60 miles to the west. The city quickly expanded, covering 1,200 acres by the beginning of the Late Formative, shortly after 400 B.C. As he mapped the site’s growth, Pool discovered that the newly dominant Tres Zapotes didn’t look much like its predecessors, San Lorenzo and La Venta. They had both been organized around one outsized and opulent central plaza. In Tres Zapotes, however, Pool identified four separate plazas evenly spaced throughout the city, each about half a mile apart and ranging from about four to nine acres in size. “No one of these plaza groups is dramatically larger than the others,” Pool says. He also discovered that their layouts are nearly identical. Each has a temple pyramid on its west side, a long platform along its north edge, and a low platform set on an east-west line through its middle. According to John Clark, an archaeologist at Brigham Young University who studies the Formative period, “The site pattern is completely different from anything else I know for an Olmec site.” It’s so different, in fact, that archaeologists have dubbed the Late Formative culture at Tres Zapotes “epi-Olmec.”

Pool wondered if the seat of power in Tres Zapotes had moved from plaza to plaza over time, perhaps as the various groups jockeyed for control. But when he radiocarbon dated material from middens behind each plaza’s long mound, he discovered that they had all been occupied at the same time, from about 400 B.C. to A.D. 1. The ceramics Pool recovered from the different plazas were similar in style and technique, providing more evidence that they were occupied simultaneously—and that no one group dominated the others. Pool realized he wasn’t looking at signs of political conflict. He was looking at signs of political cooperation. “There was a change in political organization from one that was very centralized, very focused on the ruler,” he says, “to one that shared power among several factions.”

Pool is careful to point out that Tres Zapotes wasn’t a democracy as we think of it today. “I’m not saying that everybody in this society was getting together and agreeing on things,” he says. “It may have been more like an oligarchy.” But there are signs that Tres Zapotes may have been more equitable than traditional Olmec capitals. For instance, the elites in the plazas and the commoners who lived outside of them all used similar styles of pottery. “Everyone pretty much has the same range of stuff,” says Pool. He has discovered that, unlike at La Venta and San Lorenzo, the leaders of Tres Zapotes didn’t import exotic goods, and so weren’t reliant on trade networks. Craft workshops attached to the plazas show that the people at Tres Zapotes made ceramics and obsidian tools locally. “All that,” says Pool, “suggests a more flattened kind of sociopolitical hierarchy than you see elsewhere.

“With the declining importance of the nobility and other kinds of elites, you get more economic equality,” says Richard Blanton, an anthropologist at Purdue University who was among the first to propose that such societies may have existed in Mesoamerica. Cooperative governments also tend to produce different kinds of art than monarchies, Blanton says. Rather than monuments and tombs that glorify individual rulers, polities with shared power tend to separate the idea of authority from any particular person. That’s what Pool sees at Tres Zapotes. The most elaborate monument he’s found from the Late Formative period shows a ruler emerging out of the cleft brow of a monster to connect the underworld, the earth, and the sky. “This reasonably represents the ruler as the axis mundi, or the central axis of the earth,” says Pool. This is a common theme in Olmec iconography. But unlike earlier Olmec art, including the colossal heads, the carving is not naturalistic and doesn’t seem to represent a particular ruler. “The focus seems to be less on the person than it does on the office,” Pool says. At Tres Zapotes, the idea of rulership, rather than an actual monarch, was what mattered.

Pool can’t say exactly why the people of Tres Zapotes first decided to experiment with a shared power model. Perhaps the collapse of trade routes doomed the monarchy at La Venta and undermined that form of authority. Or maybe the mass migration into the city that researchers have posited required that the factions cooperate to build a new, stable home. But whatever the cause, Pool says, this unprecedented level of cooperation in an Olmec city helped it outlast every other outpost of its culture. “What Tres Zapotes has shown is that even though there were Olmec centers that collapsed, Olmec culture also evolved,” Pool says. Archaeologists today may define this change as epi-Olmec, but for the people living through it, the transition was smooth and continuous. “The Olmec culture didn’t just vanish overnight,” Clark agrees. At Tres Zapotes, he says, “They’re hanging on and modifying it and trying to save it.”

Even as Tres Zapotes tried out a new form of government, it made room for symbols of the past: Two colossal heads, as well as other pieces of older, more authoritarian Olmec art, occupied prominent places in plazas throughout the city’s height. “There are aspects of their culture that [the epi-Olmecs] are trying to hold onto,” Pool says. The older heads “are essentially royal ancestors that provide a legitimate claim to authority”—even though that authority was now shared among several different groups.

This system of cooperative government worked for a long time—about 700 years. “But eventually,” Pool says, “it just falls apart.” Between A.D. 1 and 300, shared power slowly gave way to individual rule again. The once-standardized plazas were built over with new architectural styles and layouts, each taking on a discrete form and asserting its individuality rather than projecting harmony and cooperation. Carved stone monuments dating to around the first century A.D. found just outside Tres Zapotes show a standing figure with another person sitting in front of him, a resurgence of the artistic themes of individual ruler and subject. Over the next several centuries, Tres Zapotes slowly declined and the Gulf Coast’s cultural center of gravity shifted toward sites in central Veracruz. Meanwhile, the monarchy-obsessed Maya rose to dominate lands farther south. After 2,000 years of adaptation and survival, Tres Zapotes slowly faded into obscurity and was eventually abandoned.

Pool still doesn’t know why the city gave up on its experiment in shared governance. He does speculate that it’s possible that Tres Zapotes’ power model splintered as its regional dominance declined. Pool is sure, however, that the transition wasn’t sudden, as with San Lorenzo or La Venta. According to Pool, when the end came for Tres Zapotes, it was “a soft landing.”

The surprising thing is not that Tres Zapotes’ era of shared power came to an end, says Blanton. It’s that it survived for as long as it did. “It is very difficult to build and sustain these more cooperative kinds of polities,” he says. “Autocracy is always an alternative.” Tres Zapotes may have ended as it began: with a king. But for nearly 700 years in between, it tried something different. Monarchy gave way to cooperation, wealth became more evenly distributed, and an entire culture, for a time, redefined what government and leadership could mean.