Top 10

Richard III’s Last Act

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

In September 2012 a skeleton discovered beneath a parking lot by University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) offered tantalizing but circumstantial clues—including its location, battle wounds, and spinal deformity—connecting it with King Richard III (r. 1483–1485). “Of course we had to prove it through proper scientific analysis,” says Richard Buckley, director of ULAS. So the remains were subjected to radiocarbon dating, stable isotope analysis, and detailed osteological examination.

In September 2012 a skeleton discovered beneath a parking lot by University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) offered tantalizing but circumstantial clues—including its location, battle wounds, and spinal deformity—connecting it with King Richard III (r. 1483–1485). “Of course we had to prove it through proper scientific analysis,” says Richard Buckley, director of ULAS. So the remains were subjected to radiocarbon dating, stable isotope analysis, and detailed osteological examination.

All results were consistent with historical accounts, and genetic comparison with two descendants of Richard’s bloodline provided a final verdict in February. “We could say that beyond reasonable doubt it was Richard III,” says Buckley.

Shortly after the identity of the remains was confirmed, another group of archaeologists announced that they had pinpointed the precise location of Bosworth Field, where Richard met his end, a mile away from the location where the battle was originally believed to have taken place. Among the finds there were a cache of weapons, cannonballs, armor, and a silver badge that may have been carried by one of Richard’s knights.

Cast by both historians and Shakespeare as twisted in both mind and body, Richard III hasn’t received this much attention in more than 500 years. “Of course, what we can’t do is say anything about his character,” says Buckley. “That’s what everybody always wants to know.”

|

Sidebar:

|

Parking Lot Pay Dirt

|

Homo erectus Stands Alone

By ZACH ZORICH

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

The analysis by paleoanthropologists of a skull dated to 1.8 million years ago, found at the site of Dmanisi in Georgia, could result in the recategorization of ancient hominin species. The skull, originally excavated in 2005, is the fifth one to be found within a 100-square-foot area. Taken together, these five individuals, although highly variable in appearance, are believed to provide a snapshot of Homo erectus, the first human species to migrate out of Africa.

The most recently discovered skull has a small brain case, roughly half the size of that of the average modern human, but a very large face. According to existing standards of classification, if those two parts of the skull had been found as fragments at separate sites, they may have been assigned to two different species, says Christoph Zollikofer, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Zurich. Now, he says, the fact that the five skulls differ widely shows that Homo erectus individuals were far more diverse in appearance than many scientists had thought.

Based on the range of skull shapes and sizes from Dmanisi, Zollikofer believes that all Homo fossils that date to roughly 1.8 to 1.5 million years ago likely belonged to a single human species. All African fossils of that time period, he explains, variably attributed to Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, and Homo ergaster, should be considered part of the species Homo erectus.

A Wari Matriarchy?

By ZACH ZORICH

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

At the center of Castillo de Huarmey in northern Peru is a burial complex where Milosz Giersz and a team of archaeologists from the University of Warsaw and the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru uncovered chambers containing the remains of three, or possibly four, royal women of the Wari Empire. They were accompanied by 40 noblewomen buried in a sitting position, seven sacrificed individuals whose bodies had been thrown over the seated burials, and more than 1,300 artifacts, including ear ornaments typically worn by royal men and weaving tools made of gold and silver.

“This is the first time in an archaeological excavation that we have found a tomb full of prestige goods related to Wari women,” Giersz says, adding that cotton and camel-wool textiles also found as grave goods were considered by the Wari to be more valuable offerings than gold. Giersz estimates that the tomb dates to A.D. 750. Burials of royal men have been found at the site, but thus far not in chambers of this size. The tomb could answer questions about the roles that women played at the highest levels of Wari society.

Roman Buildings Grow Up

By JASON URBANUS

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

Eleven miles east of Rome, in the ancient city of Gabii, archaeologists unearthed a building complex that may represent the earliest instance of Roman monumental architecture. This enormous structure, dating to the fourth or third century B.C., was excavated by a team from the University of Michigan and predates most of the grand monuments of Rome itself. The large stone–block construction sprawls across three man-made terraces, enveloping a space of more than 22,000 square feet—roughly an entire ancient city block. The exceptional design features colonnades, geometrically patterned floors, wall paintings, and a grand staircase.

Because the site has not yet been fully excavated, it remains to be determined whether this complex served a public or private function. Regardless of the outcome, according to Marcello Mogetta, managing director of the Gabii Project, this structure is unprecedented within the archaeology of the Roman Republic—a period traditionally esteemed for its rejection of opulence and grandeur. If the complex is a private residence, its sheer size makes it unlike any contemporary aristocratic Roman house in Italy, and larger than even those of Pompeii and Rome.

“If the interpretation as a public building were confirmed, we would be moving into uncharted territory,” says Mogetta, adding that political buildings of the time were still being built with wooden posts and perishable materials. “The Gabii structure would provide a much earlier example of the desire for monumental architecture in a civic context.”

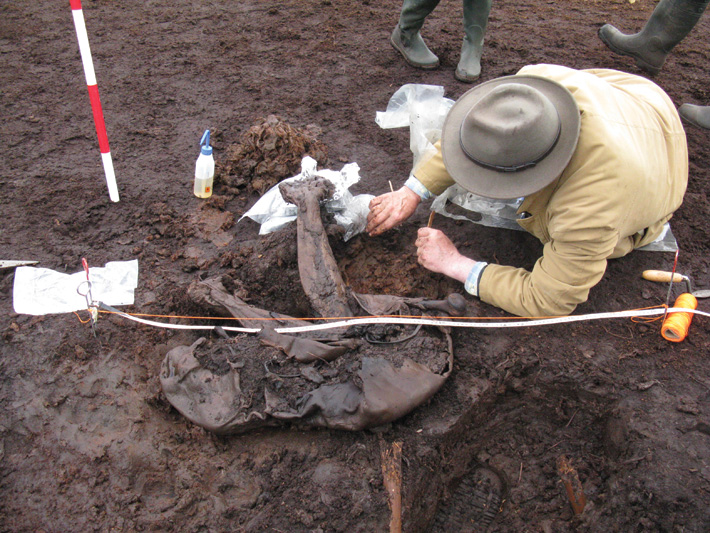

Oldest Bog Body

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

When radiocarbon dating results came in on a body discovered by a peat cutter in the middle of Ireland’s Cashel Bog, they elicited surprise. “Cashel Man” is the oldest fleshed bog body in Europe, predating the former holder of that title by at least 600 years. Cashel Man lived in the Early Bronze Age, around 2000 B.C., and clearly died a violent death. CT scans revealed that his spine was shattered in two places, a sharp blow had broken his arm, and he had been struck multiple times in the back with an ax. Archaeologist Eamonn Kelly of the National Museum of Ireland believes that Cashel Man’s burial on an ancient regional border, and the nature of his injuries, are evidence that the practice of sacrificing young men—a ritual connected with kingship and sovereignty well known from the Iron Age (500 B.C. to A.D. 400)—is 1,500 years older than previously thought.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement