From the Trenches

Something New for Sutton Hoo

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, February 13, 2017

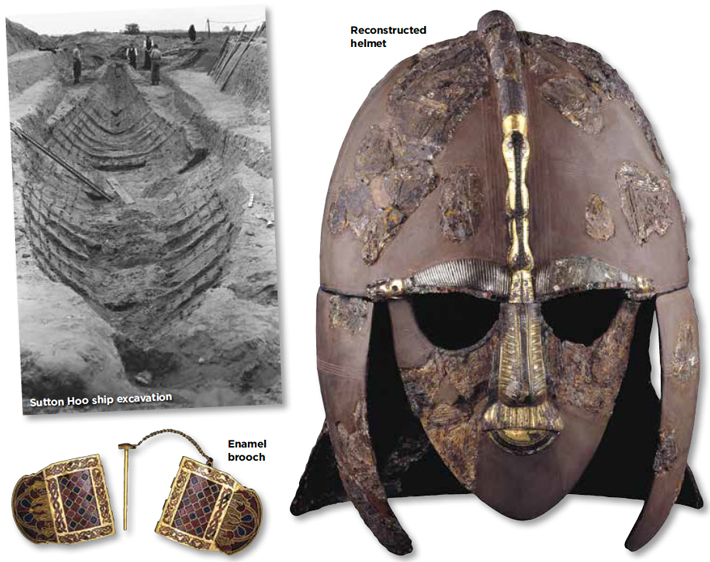

Even after almost eight decades, the Sutton Hoo ship burial is still providing researchers with new information that continues to underscore the wealth, reach, and prestige of East Anglia’s Anglo-Saxon kings. When the seventh-century grave was first excavated in 1939, archaeologists discovered a treasure trove of material: gold and garnet jewelry, ceremonial armor, silverware, and other exotic goods. Among the hundreds of objects collected at the time were several clumps of a black organic substance. For decades experts believed that this was a tar-like compound that was used in the waterproofing and maintenance of ancient ships.

However, a research team from the British Museum and the University of Aberdeen recently reanalyzed this material using modern technology including mass spectrometry and infrared spectroscopy. They determined that the black clumps were not pine tar, but actually bitumen, a semisolid form of petroleum. Furthermore, the geochemical signature of the bitumen indicates that it is from a Middle Eastern source, most likely Syria. In the ancient world, bitumen was highly valuable and had various uses, from medicine to waterproofing to use as an adhesive. At this point archaeologists are not quite sure why the bitumen was included in the burial, but its presence there demonstrates that the kings of East Anglia had access to an array of luxury items from widespread trade markets. British Museum researcher Rebecca Stacey says, “This new finding reinforces what we know about the intercontinental connections of East Anglia in the seventh century, and forces a reconsideration of the significance of this material in the burial assemblage.”

Secret Spaces

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, February 13, 2017

To rid himself of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and to (attempt to) fulfill his quest for a son and heir, King Henry VIII needed a divorce. But for a Roman Catholic, this wasn’t an option, so the frustrated monarch forced the hand of the Archbishop of Canterbury and was granted his wish. This decision would have lasting consequences.

To rid himself of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and to (attempt to) fulfill his quest for a son and heir, King Henry VIII needed a divorce. But for a Roman Catholic, this wasn’t an option, so the frustrated monarch forced the hand of the Archbishop of Canterbury and was granted his wish. This decision would have lasting consequences.

The ties that once bound England to the papacy were severed, the English monarch became the head of the new church, and monasteries across the country were dissolved, their riches and land confiscated. Many Catholic priests were forced into hiding to avoid persecution and even execution, and to protect them, some Catholic loyalists fashioned hiding places called “priest holes” in their country homes. At the Throckmorton family’s Coughton Court in Warwickshire, one of these priest holes has now been brought out of hiding through 3-D imaging. Says Christopher King of the University of Nottingham, the work at Coughton “allowed us to create the first accurate record of the priest hole with high-resolution data. More importantly, by scanning the priest hole alongside the rest of the structure, and putting the two scans together, we can demonstrate how it has been fitted inside this complex structure—hidden in a former stair-turret and located between two floor-levels, helping to conceal it.”

Off the Grid

By MALIN GRUNBERG BANYASZ

Monday, February 13, 2017

Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal Archaeology and History Complex, in Old Montreal, Quebec, sits right on top of the city’s birthplace. This location is the site of more than 1,000 years of human activity, beginning when indigenous peoples made camp here between the Little Saint Pierre and the Saint Lawrence Rivers. The first French settlement on the site, Fort Ville-Marie, was created in 1642 as the home for some 50 settlers, including founders Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve and Jeanne Mance. The museum, which was built in 1992 as part of the celebration to mark Montréal’s 350th anniversary, has both permanent and temporary exhibits, including traveling displays from all over the world. Pointe-à-Callière Project Manager Louise Pothier says, “Pointe-à-Callière is a site museum unlike any other in Canada. It combines a number of archaeological sites illustrating the city’s growth over the years: Fort Ville-Marie, the first Catholic cemetery, the first public marketplace, and even Canada’s first stone collector sewer, which was laid in the bed of the Little Saint Pierre River in 1832, and which is now open for visitors to walk through. Few large cities in the world have the privilege of being able to exhibit strata from their past in this way. Montrealers are very proud to preserve this rich heritage and share it with visitors.”

THE SITE

THE SITE

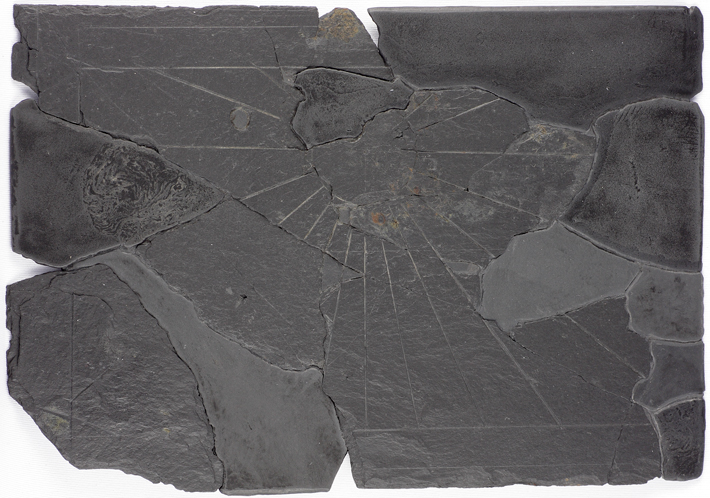

In order to protect the remains of Fort Ville-Marie, a pavilion is being built that will open in May 2017. An exhibition there, Where Montréal Was Founded, will honor Montreal’s founders. The installation will remember the first Mass held at the establishment of Fort Ville-Marie. Visitors will be able to walk across a glass floor overlooking the remains of the fort, as well as a fire pit predating the city, a seventeenth-century well, the basement of what may have been a guardhouse, several of the fort’s palisades, and the foundations of a metalworking shop. Numerous artifacts will be on display, including a slate sundial thought to be the oldest in North America, objects reflecting religious practices and everyday life, munitions and gun parts, and trade items.

WHILE YOU'RE THERE

The Pointe-à-Callière museum is the best place to begin a visit to Montréal if you want to understand its beginnings, and Old Montreal still has an antique flavor, with its horse-drawn carriages and cobblestone streets. Other notable locations such as the Notre-Dame Basilica, the Hôtel de Ville (City Hall), the Old Port, and the Bonsecours Market are just a few of the things to see in the city. After taking in the sights, be sure to enjoy one of many sidewalk cafes overlooking the Saint Lawrence River.

Revisiting Montezuma Castle

By ERIC A. POWELL

Monday, February 13, 2017

At Montezuma Castle National Monument in central Arizona, a village composed of two cliff dwellings was abandoned sometime in the fourteenth century. Archaeologists who dug the dwellings in the 1930s found evidence for a destructive fire, but concluded that the village burned long after it was vacated. This interpretation clashed with Native American accounts. Hopi people with strong ties to the site recount that their ancestors were attacked and forced to flee, while local Apache oral history holds that ancestral Apaches and their allies stormed the village and set it ablaze.

National Park Service archaeologist Matthew Guebard recently collected new data at one of the dwellings, and reviewed the original excavation reports in an effort to reconcile the conflicting accounts. Dating of charred plaster walls determined that the fire occurred sometime between 1375 and 1395, and analysis of pottery demonstrates that some of the ceramics found there had been made during this period. That led Guebard to believe that the village had been occupied until the time it was destroyed. His reexamination of the remains of four people unearthed in the 1930s shows they have skull fractures, cuts, and singe marks that indicate they were likely killed during an attack that coincided with a catastrophic fire. “The abandonment of the site was inextricably tied to a violent event,” says Guebard, who believes the archaeological evidence supports the Native American version of the ancient village’s demise.

Digging up Digital Music

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Monday, February 13, 2017

Archaeologists think of stone tools in terms of “technologies”—the particular ways that they were made and used—that help us understand the cultures that produced them. Today we have our own technologies, but they come and go at a vastly different pace. Their life spans are measured not in thousands of years, but in months and even days. To modern digital technology, 65 years is an eon.

The late 1940s and early 1950s saw the birth of the computer age, and one of its nurseries was the Computing Machine Laboratory in Manchester, England, led by logician and cryptanalyst Alan Turing. Lesser known among the many innovations to come out of the lab—including “Baby,” the first stored-program computer—are the first melodies generated by computer, the most distant ancestor of modern electronic music. Recently, a philosopher and a composer collaborated to analyze and restore the earliest known recording of these melodies—a founding artifact of the age of digital music.

According to Jack Copeland, philosopher and director of the Turing Archive for the History of Computing at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand, Turing’s Mark I computer generated its first “notes” in 1948. The machine had a hooter to provide auditory feedback, a middle C-sharp that Copeland describes as “like a cello playing underwater,” which could produce different notes when activated in different patterns. In 1951, a schoolteacher named Christopher Strachey convinced Turing to let him program the lab’s next machine, the Mark II. Strachey, who became one of the world’s foremost programmers, coaxed it to play “God Save the King,” England’s national anthem. Turing’s response: “Good show.” (A computer in Melbourne was doing similar work around this time as well.)

The same year, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) recorded three melodies from the machine: the anthem, “Baa Baa Black Sheep,” and Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood.” The analog recording charmingly captures the voices of people in the room: “The machine’s obviously not in the mood,” a woman jokes during the Miller tune. The BBC likely destroyed its copy, but Frank Cooper, an engineer at the lab, asked for a souvenir version—a black, 12-inch acetate record that survives in private hands. “They knew how priceless this disc was,” says Copeland, “so they held onto it.”

The same year, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) recorded three melodies from the machine: the anthem, “Baa Baa Black Sheep,” and Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood.” The analog recording charmingly captures the voices of people in the room: “The machine’s obviously not in the mood,” a woman jokes during the Miller tune. The BBC likely destroyed its copy, but Frank Cooper, an engineer at the lab, asked for a souvenir version—a black, 12-inch acetate record that survives in private hands. “They knew how priceless this disc was,” says Copeland, “so they held onto it.”

A digital copy of the record was later made by the British Library, and Copeland and composer and musician Jason Long analyzed it. In studying the frequencies on the recording, they found some notes that the computer would not have been able to produce. Copeland and Long thought about what might have created these “impossible notes,” including errors in the speed of the BBC’s portable disc cutter. The researchers wrote a simple program and found that, sped up just a few percent, the recording perfectly matched the notes the computer could produce. With a little more cleaning up, the machine’s original voice emerged. “It just sounded right for the first time,” says Copeland. “We never knew it sounded wrong until we heard it right. We were able to dig up the original sound.” Although it is only sound, it is a compelling reflection of its time.

Today, early artifacts of the digital age—chips, computers, equipment, diagrams, technical documents, even programs—are important historical records of developments that shape modern life, and they are at risk of being forgotten or destroyed. “The digital world moves so fast, it’s constantly refreshing itself to such a degree that it is creating all kinds of opportunities for archaeology,” says Christopher Witmore, an archaeologist at Texas Tech University who both works on ancient sites in Greece and writes about the archaeology of the more recent past. “Archaeology is rich enough to encompass all of these things.”

To hear the restored recording of Turing’s Mark II, click below.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

The First American Revolution

Kings of Cooperation

The Road Almost Taken

Letter from Philadelphia

From the Trenches

Digging up Digital Music

Off the Grid

Revisiting Montezuma Castle

Secret Spaces

Something New for Sutton Hoo

A Surprise City in Thessaly

Zinc Zone

Behind the Curtain

Royal Gams

A Mix of Faiths

Neolithic FaceTime

Bathing, Ancient Roman Style

The Church that Transformed Norway

Siberian William Tell

A Traditional Neanderthal Home

Artifact

Self-expression in the Bronze Age

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement