From the Trenches

Mongol Fashion Statement

By ERIC A. POWELL

Monday, April 06, 2015

The Golden Horde, a group of Mongols who conquered much of Eastern Europe in the thirteenth century, was famously tolerant of foreign religions. Recently, however, archaeologist Zvezdana Dode of the Southern Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences completed a study of rare textiles that suggests the Mongol attitude to Christianity was sometimes more complex than simple indifference. She examined pieces of fabrics found in Mongol burials that represent Christian subjects but had been repurposed as clothing, such as a hat that depicts an upside-down Jesus flanked by two archangels. She suggests that these fabrics, likely seized from Russian churches, were not merely the spoils of war. “The Mongols were able to observe employment of icons and banners with Christian symbols by the Russian military,” says Dode. “It’s possible they interpreted these symbols as devices for supernatural warfare.” By wearing an inverted Christian motif into battle, a Mongol warrior may have thought he was neutralizing that threat.

A Shipwreck in Drydock

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Friday, April 03, 2015

One of the most spectacular shipwreck projects in Chinese underwater archaeology was the 2007 raising—intact, with the surrounding sediment—of Nanhai Number One, the wreck of a Song Dynasty merchant vessel (see the September/October 2011 feature “Pirates of the Marine Silk Road”). A 3,000-ton steel cage brought the wreck to a custom saltwater tank in a newly built museum on Hailing Island in Guangdong. The museum was completed in 2009, and full-scale excavations began in late 2013. Recently archaeologists have reached the interior of the ship, and have so far found more than 600 pieces of porcelain, 100 gold artifacts, and 5,000 bronze coins, among other items—with countless more to come. Nanhai Number One dates to between A.D. 1127 and 1279, a time when China’s ocean-based trade and exploration flourished, before the fleet was dismantled a few centuries later.

The Price of a Warship

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, April 06, 2015

A salvage excavation occasioned by the construction of a rail project crossing the Bosphorus in Istanbul, Turkey, turned up a bonanza of shipwrecks from the Byzantine era: In all, 37 have been found since 2004. Now a team of researchers has scrutinized each timber in eight of the wrecks, dating from the seventh to tenth centuries A.D., and has gained new insight into the markedly different materials used to build merchant ships and warships of the time.

A salvage excavation occasioned by the construction of a rail project crossing the Bosphorus in Istanbul, Turkey, turned up a bonanza of shipwrecks from the Byzantine era: In all, 37 have been found since 2004. Now a team of researchers has scrutinized each timber in eight of the wrecks, dating from the seventh to tenth centuries A.D., and has gained new insight into the markedly different materials used to build merchant ships and warships of the time.

The team studied six merchant round ships, powered primarily by sail, and two galley warships, powered by oar. “The merchant ships were massive and would have bludgeoned through the waves,” says Cemal Pulak of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology in College Station, Texas, “whereas the galleys are long and flexible and their timber is quite light—and they selected different types of material for that.”

Analysis of the ships’ timbers found a number of indications that the warships were built at greater expense. For example, the galleys’ planking consisted of European black pine, which would have been imported from afar, while readily available Turkey oak was used in the round ships. It is unclear whether merchant galleys of the time were built with the same high-quality materials as galley warships, as no merchant galleys from the Byzantine era have yet been found.

Analysis of the ships’ timbers found a number of indications that the warships were built at greater expense. For example, the galleys’ planking consisted of European black pine, which would have been imported from afar, while readily available Turkey oak was used in the round ships. It is unclear whether merchant galleys of the time were built with the same high-quality materials as galley warships, as no merchant galleys from the Byzantine era have yet been found.

Medieval Leather, Vellum, and Fur

By KATE RAVILIOUS

Friday, April 03, 2015

At a site soon to be a multistory parking garage in the English city of Norwich, recent excavations have uncovered an upmarket thirteenth-century tannery. In December 2014, trial trenches at this low-lying city-center location revealed temporary platforms and freshwater pits, typical of a tannery. Archaeologists also found vast numbers of goat horn-cores—the inner part of the horn—suggesting that it was mostly goatskin being processed there. “Goatskin was used to make very high-quality leather and it is possible they were making vellum, the parchment used for scrolls and books,” says lead archaeologist David Adams. The site’s location, between two monasteries, and the period it was in operation, from the 1200s to the 1500s, fit with this idea. Meanwhile, a handful of worked cat bones show that cat fur was also being produced there, perhaps for trim on hats or gloves—a common use for it in medieval Britain.

At a site soon to be a multistory parking garage in the English city of Norwich, recent excavations have uncovered an upmarket thirteenth-century tannery. In December 2014, trial trenches at this low-lying city-center location revealed temporary platforms and freshwater pits, typical of a tannery. Archaeologists also found vast numbers of goat horn-cores—the inner part of the horn—suggesting that it was mostly goatskin being processed there. “Goatskin was used to make very high-quality leather and it is possible they were making vellum, the parchment used for scrolls and books,” says lead archaeologist David Adams. The site’s location, between two monasteries, and the period it was in operation, from the 1200s to the 1500s, fit with this idea. Meanwhile, a handful of worked cat bones show that cat fur was also being produced there, perhaps for trim on hats or gloves—a common use for it in medieval Britain.

A Slice of Parasitic Life

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, April 06, 2015

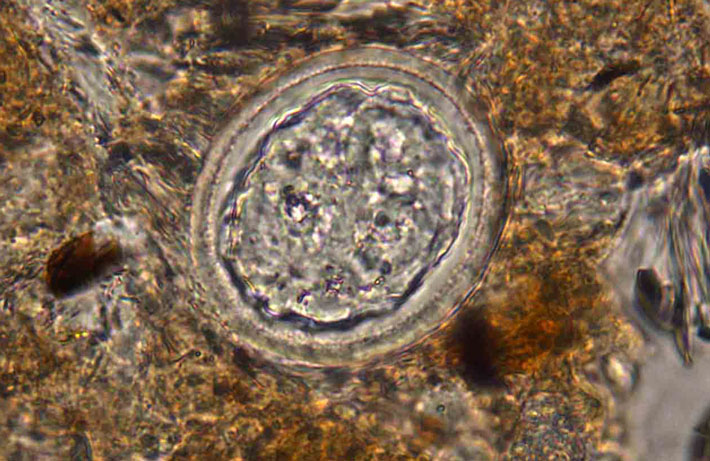

It’s hardly surprising that an Iron Age settlement in which livestock lived alongside people and open pits served as latrines would be overrun with intestinal parasites. As expected, researchers studying sediments from some of these pits at a settlement in present-day Basel, Switzerland, dating to around 100 B.C., found roundworm, whipworm, and liver fluke eggs.

It’s hardly surprising that an Iron Age settlement in which livestock lived alongside people and open pits served as latrines would be overrun with intestinal parasites. As expected, researchers studying sediments from some of these pits at a settlement in present-day Basel, Switzerland, dating to around 100 B.C., found roundworm, whipworm, and liver fluke eggs.

What makes their findings notable is the method they used. Archaeologists typically detect parasite eggs through “wet sieving,” in which soil is moistened and then strained, which allows a large volume of fill to be searched, but provides no information on where the eggs were originally located. Instead, at Basel, scientists have produced very thin slices of sediment that can be studied under a microscope, which preserves the location of the parasite eggs in their original setting. “You would expect the parasite eggs to be close to where the feces were,” says Sandra Pichler of the University of Basel, “but we found that the eggs get washed out by water and spread around. Even sediments without any fecal indicators still had parasite eggs.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

The Charred Scrolls of Herculaneum

Off The Grid

Viking Trading or Raiding?

Telecom History Deep Beneath the Pacific

How Grass Became Maize

Medicine on the High Seas

Cause of Death

A Western Wiki-pedia

Catching Fire and Keeping It

Oysters for the Earth Goddess

Ant Explorers

A Soul of a City

A Slice of Parasitic Life

The Price of a Warship

Medieval Leather, Vellum, and Fur

A Shipwreck in Drydock

Mongol Fashion Statement

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement