Latest News

-

Photo by B. Wygal

Photo by B. Wygal -

Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service

Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service -

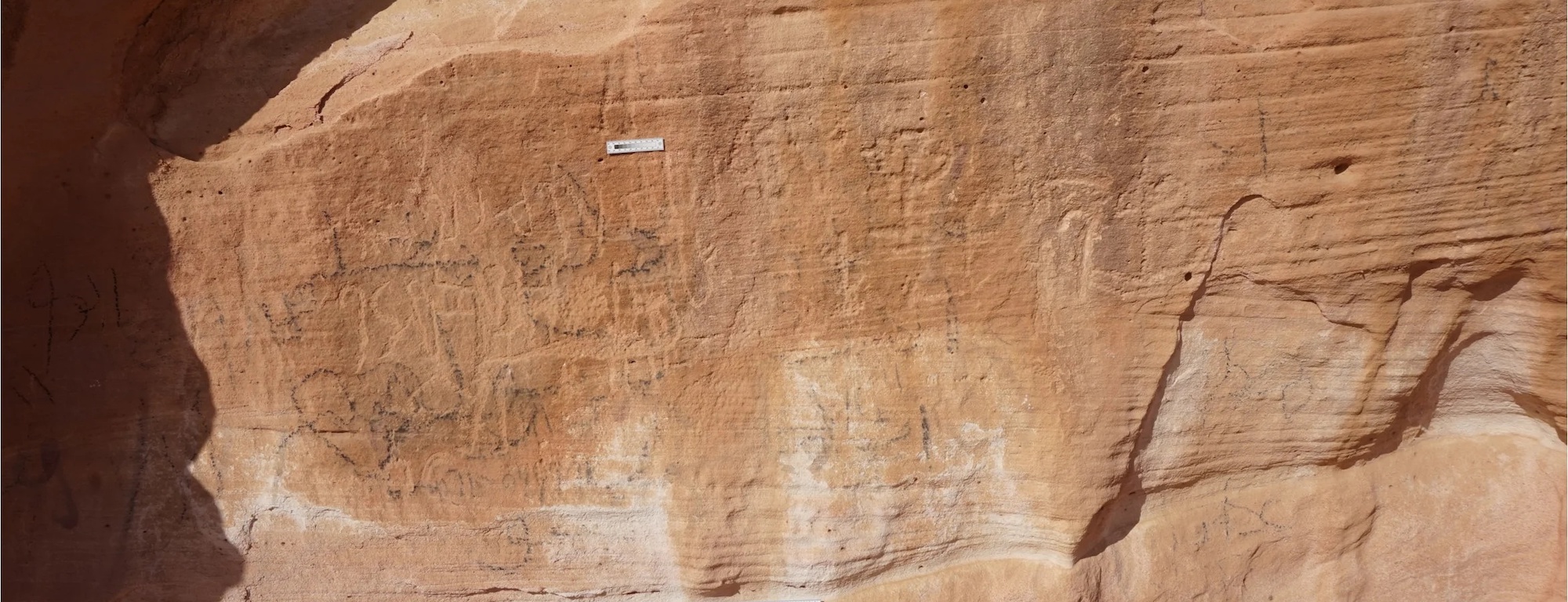

© M. Nour El-Din

© M. Nour El-Din -

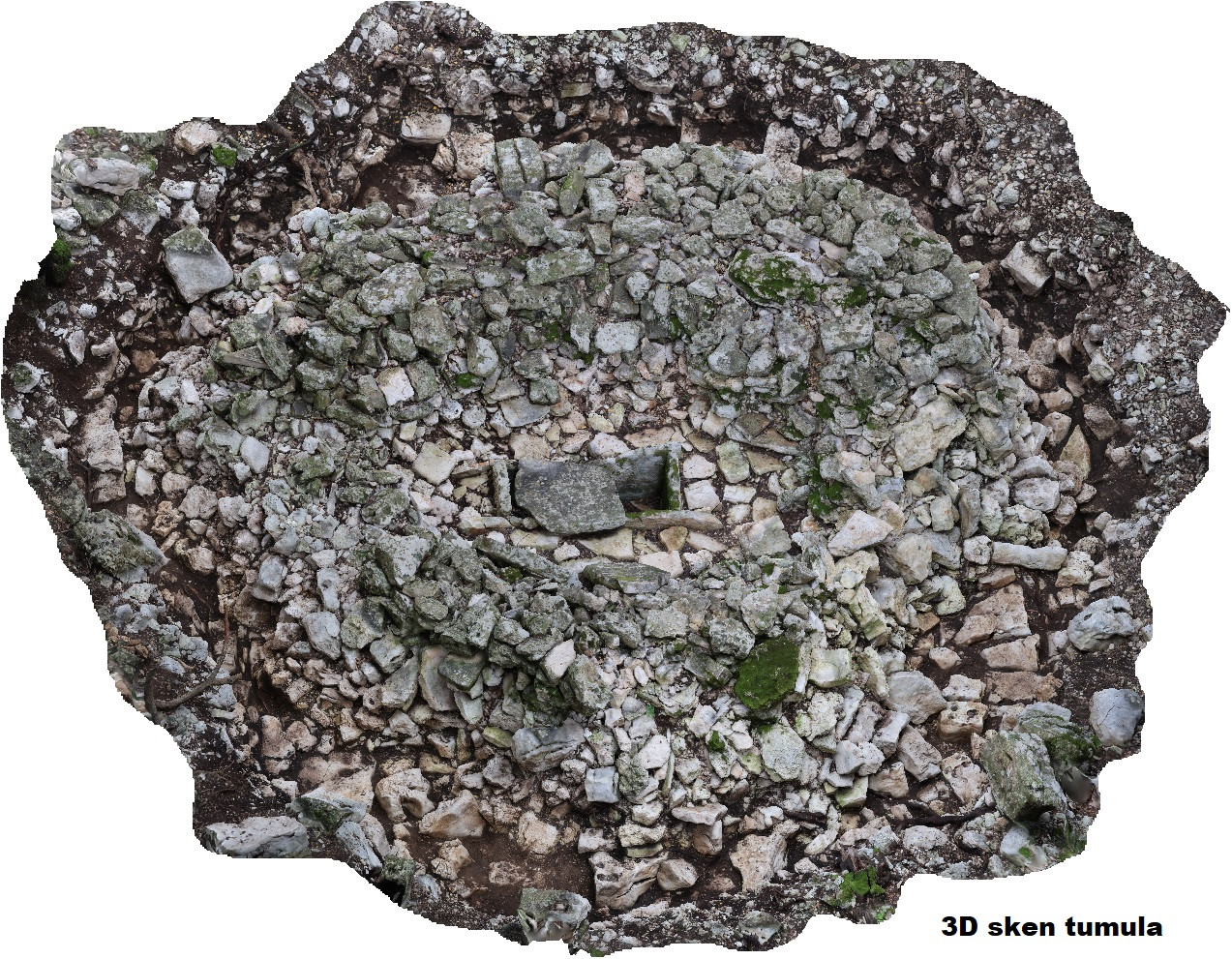

Brijuni National Park Public Institute

Brijuni National Park Public Institute

-

© Adrian Daly

© Adrian Daly -

-

-

Lukas Goldmann/Brandenburg State Office for Monument Preservation and Archaeological State Museum

Lukas Goldmann/Brandenburg State Office for Monument Preservation and Archaeological State Museum -

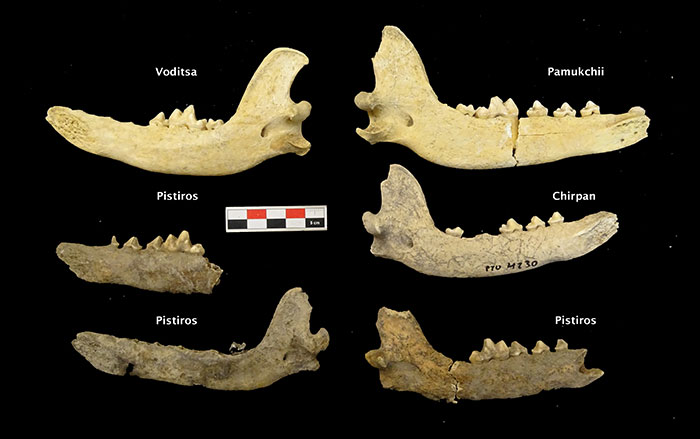

Courtesy Stella Nikolova

Courtesy Stella Nikolova -

Photograph by D. Michailidis, © K. Harvati

Photograph by D. Michailidis, © K. Harvati -

Courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History

Courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History -

Shixia Yang

Shixia Yang -

Baselland Archaeology

Baselland Archaeology -

Luis Gerardo Peña Torres, INAH

Luis Gerardo Peña Torres, INAH -

-

Angélica Triana

Angélica Triana

Loading...