From the Trenches

Norwegian Knight

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, April 09, 2018

An 800-year-old gaming piece unearthed in Tønsberg, Norway’s oldest city, has been identified as a knight used to play an early form of chess. Lars Haugesten of the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research, the excavation’s project manager, explains that the object’s shape is similar to that of chess pieces found in Arabia. It was likely made locally, however, as it was carved from reindeer antler and is decorated with a number of dotted circles, which are typical of Scandinavian designs. The piece’s protruding nose identifies it as a knight. Haugesten says it may originally have had a piece of lead embedded in it to prevent it from tipping over on a playing surface.

An 800-year-old gaming piece unearthed in Tønsberg, Norway’s oldest city, has been identified as a knight used to play an early form of chess. Lars Haugesten of the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research, the excavation’s project manager, explains that the object’s shape is similar to that of chess pieces found in Arabia. It was likely made locally, however, as it was carved from reindeer antler and is decorated with a number of dotted circles, which are typical of Scandinavian designs. The piece’s protruding nose identifies it as a knight. Haugesten says it may originally have had a piece of lead embedded in it to prevent it from tipping over on a playing surface.

Circle of Life

By ZACH ZORICH

Monday, April 09, 2018

A rare circular burial found at the site of Tlalpan in southern Mexico City holds the remains of 10 males and females ranging in age from infancy to adulthood. The burial dates to approximately 2,400 years ago, a period when state-level societies were beginning to take shape in the Valley of Mexico. Some of the skeletons in the 6.5-foot-diameter grave show signs of intentional skull deformation and tooth filing, which were common practices in later Mesoamerican civilizations. The arrangement of the skeletons suggests to archaeologists that the burial could symbolize the stages of life, progressing from young to old.

Conquistador Contagion

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, April 09, 2018

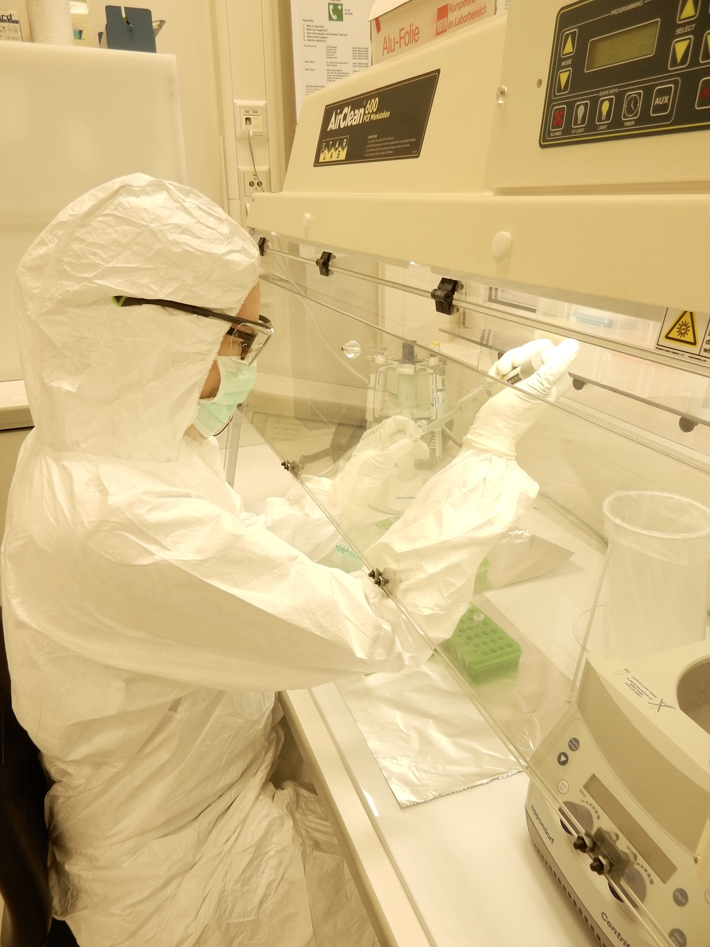

A pathogen possibly responsible for one of several catastrophic sixteenth-century epidemics in Mexico has been identified in DNA taken from the teeth of several of its victims. The 1545 huey cocoliztli, or “great pestilence,” as it was called at the time in the Nahuatl language, raged through Mesoamerica 25 years after the Spanish arrived, killing tens of millions. Working with genetic material from 29 individuals buried in the only known cemetery from the 1545 outbreak, a team from Germany’s Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History has discovered the presence of Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi C, a bacterium that causes paratyphoid fever. It’s rare today but has a high mortality rate if untreated. Max Planck’s Christina Warinner says, “People have been wondering about the cause of this epidemic for 500 years.”

There are few human remains tied conclusively to the 1545 cocoliztli. “One of the big mysteries in Mesoamerican archaeology is, where are all the epidemic victims?” Warinner says. “There’s so much historical evidence of it, but this cemetery was really the first definitive epidemic cemetery that’s been found.” Around 2006, she began working at the sixteenth-century Mixtec village site of Teposcolula-Yucundaa in Oaxaca, where Mexican archaeologists had recently uncovered graves dug in the central square. Bodies had been buried in the grand plaza, the town’s administrative center, with as many as five or six individuals often interred in one grave. “Most people buried there are young adults—really at the height of health—and there was no evidence of trauma,” she says. “It suggests a catastrophic event.” The town was abandoned in 1552, so the team knew the graves must date to the 1545 epidemic.

While researchers could now study the remains of victims, they needed technology that would screen massive amounts of genetic data without knowing what pathogen to look for. They employed a tool called MALT, which uses an algorithm to search through a database of all bacterial pathogens and DNA viruses for which genomic data is available. “In a very long list of mostly environmental bacteria,” explains Åshild Vågene, also of Max Planck, “we saw Salmonella enterica as a potential pathogenic organism. We looked at this DNA a bit closer and it seemed to belong to Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi C, which is one of the few bacterial causes of enteric fever.”

While researchers could now study the remains of victims, they needed technology that would screen massive amounts of genetic data without knowing what pathogen to look for. They employed a tool called MALT, which uses an algorithm to search through a database of all bacterial pathogens and DNA viruses for which genomic data is available. “In a very long list of mostly environmental bacteria,” explains Åshild Vågene, also of Max Planck, “we saw Salmonella enterica as a potential pathogenic organism. We looked at this DNA a bit closer and it seemed to belong to Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi C, which is one of the few bacterial causes of enteric fever.”

Vågene and Warinner point out that Salmonella enterica should be regarded as just one potential cause of the 1545 epidemic in this particular area of southern Mexico, rather than, as some have reported, the single cause of death throughout Mesoamerica at the time. They advise that their methods could miss other potential killers, such as viral hemorrhagic fever, an RNA virus suggested as a cause of the epidemic by microbiologist Rodolfo Acuña-Soto of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “The identification of Salmonella in human remains in Oaxaca is a remarkable observation,” Acuña-Soto states. “But, unfortunately, it does not solve the problem of the population collapse caused by the cocoliztli epidemic of 1545. Their findings are probably part of the answer, but not the answer.”

The scholars would all agree that the conditions for disease in Mexico in the sixteenth century were ideal. Warinner explains that, in addition to hundreds of boats arriving in Mexico each year carrying Europeans who were often quite ill, there were also the combined effects of warfare, political upheaval, and the sudden introduction of livestock. “It’s very clear there is a high background of disease,” Warinner says. Still, she argues, such a high rate of death points to a single culprit, and she believes Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi C could be it. “We do have discrete epidemics,” she adds. “It’s not a slow burn. These are really punctuated, massive events.”

Off the Grid

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, April 09, 2018

Archaeology at southern Oregon’s Fort Rock Cave is central to debates on when the Great Basin region was first colonized by Paleoindian peoples. In 1938, archaeologist Luther Cressman discovered dozens of sagebrush bark sandals beneath a layer of ash that were eventually radiocarbon dated to between 9,000 and 11,000 years old. The cave also produced projectile points from the Western Stemmed Tradition, a Paleoindian culture thought to have emerged around 11,000 B.C. In the 1970s, Cressman’s student Stephen Bedwell reported finding tools in Fort Rock Cave going back even further, to 15,000 years ago, a date dismissed as far-fetched by most researchers. However, recent evidence of a nearly 15,000-year-old occupation at nearby Paisley Caves prompted a team from the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History to reexamine the site. “Bedwell’s date seemed reasonable to dismiss as long as we knew people weren’t here that early,” explains Tom Connolly, director of archaeological research at the museum. “But with the proven antiquity of nearby Paisley Caves, it was a question worth revisiting.” Sadly, damage from looting and agricultural interference over the years has made it potentially impossible to find remaining cultural deposits in the cave to settle the question definitively. “We don’t have evidence from Fort Rock Cave that matches the antiquity of Paisley,” Connolly says, but visitors will nonetheless find themselves in a place that sheltered some of the area’s first residents.

THE SITE

The cave is a large rock shelter cut into a volcanic outcrop at Fort Rock State Park, in Oregon’s Lake County. It was first created by erosion from an ancient pluvial lake that was gone by the time the first people arrived. The Oregon Parks and Recreation Department offers a limited number of guided tours of the cave from May through July, by reservation. Reservations are available now for 2018, with a maximum of 10 visitors per tour, at a cost of $10 per person. Interested travelers should visit the department’s website for further information.

WHILE YOU'RE THERE

WHILE YOU'RE THERE

Because Paleoindian sites in the area, including nearby Paisley and Connley Caves, are so fragile, ask your tour guide about how best to visit sites of archaeological significance. Travelers hoping to immerse themselves in the landscape of some of the first indigenous Oregonians can drive around 40 miles north to the Newberry National Volcanic Monument and Paulina Lake, which offers some of the area’s best fishing and camping, and on whose shores archaeologists have found evidence of 9,500-year-old dwellings.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Conquistador Contagion

Off the Grid

Circle of Life

Norwegian Knight

A Night Out in Leicestershire

The Pirate Book Club

Alternative Deathstyles

Afterlife Under the Waves

No Dice Left Unturned

A Mark of Distinction

Early Buddhism in India

A Bronze Age Landmark

Time’s Arrow

We Are Family

World Roundup

Taino DNA, island Etruscans, IRA buttons, gate to the afterlife, and the last wild horses

Artifact

Man of the hours

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement