From the Trenches

Conquest and Clamshells

By ZACH ZORICH

Monday, August 11, 2014

On the north coast of Peru near the Chira River, the beach is made up of a series of ridges—sand dumped by fierce El Niño storms—big enough to be seen in satellite images. Dan Sandweiss of the University of Maine believes that these ridges used to be larger and more numerous. His research team investigated enormous deposits of clamshells on the coast and showed that, for more than 5,000 years, people had been harvesting huge amounts of shellfish there. The shells were then discarded on the beach as garbage, with the effect of helping to stabilize the sand and keep it from being blown or washed away by the relentless winds and surf. In 1532, however, the Spanish Conquest brought disease and economic reorganization that left the area depopulated. Without anyone remaining to discard clamshells on the beach, the huge sand dunes they once solidified have, over time, been reduced to nothing more than a string of sand piles—showing just how much human presence, and absence, can shape landscapes. The lesson, according to Sandweiss, is that “whatever we do, it has unintended consequences.”

On the north coast of Peru near the Chira River, the beach is made up of a series of ridges—sand dumped by fierce El Niño storms—big enough to be seen in satellite images. Dan Sandweiss of the University of Maine believes that these ridges used to be larger and more numerous. His research team investigated enormous deposits of clamshells on the coast and showed that, for more than 5,000 years, people had been harvesting huge amounts of shellfish there. The shells were then discarded on the beach as garbage, with the effect of helping to stabilize the sand and keep it from being blown or washed away by the relentless winds and surf. In 1532, however, the Spanish Conquest brought disease and economic reorganization that left the area depopulated. Without anyone remaining to discard clamshells on the beach, the huge sand dunes they once solidified have, over time, been reduced to nothing more than a string of sand piles—showing just how much human presence, and absence, can shape landscapes. The lesson, according to Sandweiss, is that “whatever we do, it has unintended consequences.”

Sounds of the Age of Aquarius

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Monday, August 11, 2014

In 2009, California state archaeologist E. Breck Parkman sifted through the charred and weathered remains of Burdell Mansion in northern California’s Olompali State Historic Park (“Digging the Age of Aquarius,” July/August 2009). The mansion had been home to a hippie commune known as “The Chosen Family,” which was loosely associated with the Grateful Dead and other prominent countercultural figures, for two years before the mansion burned down and the group disbanded in 1969. Among the finds there were 93 vinyl records. The records were without sleeves and, in almost all cases, labels. Parkman set out to identify them. He tried to play a few, without luck, and scrutinized the surviving labels for clues, such as stray words or a distinctive color scheme. He also examined codes stamped on the record and even measured track lengths to compare the sequences with known albums. He has identified 53 so far, which range from the expected (the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Nina Simone) to the markedly more mainstream (Judy Garland, Barbra Streisand, Burl Ives). The identifications confirm the surprising diversity of age and taste among the commune dwellers.

Your Face: Punching Bag or Spandrel?

By ZACH ZORICH

Monday, August 11, 2014

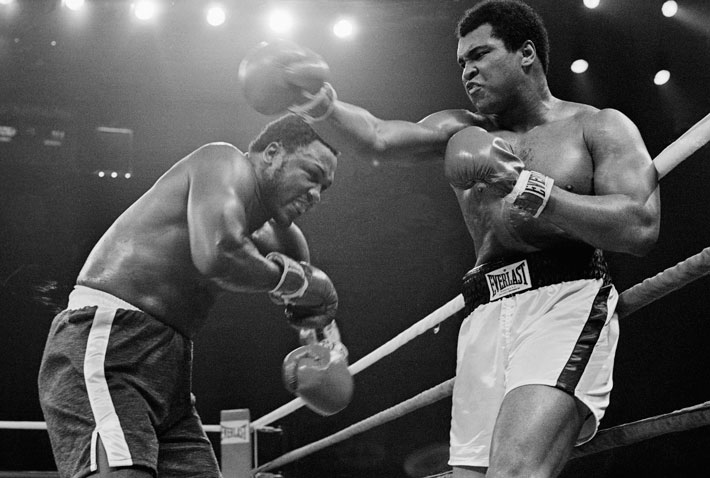

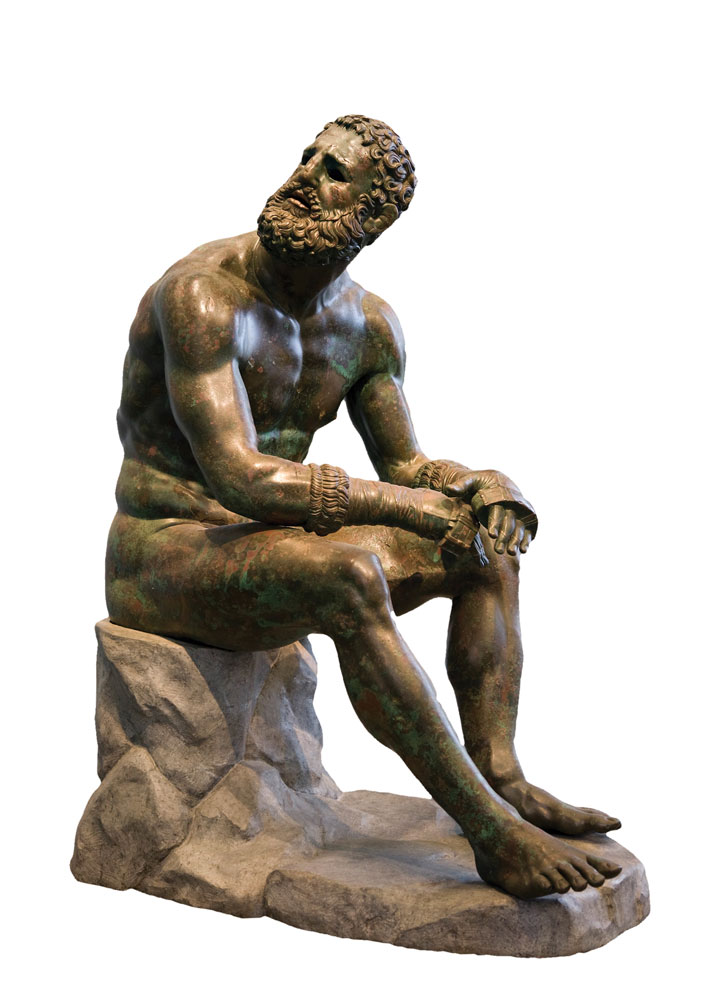

When advancing a new idea about human evolution, it is best to be prepared for a bloody fight. This lesson was recently learned by biologist David Carrier and emergency room physician Michael Morgan, both of the University of Utah, when they published a paper theorizing that the human face looks the way it does, in part, because it evolved to take a punch. Carrier and Morgan examined emergency room statistics from Western societies and found that fights between untrained combatants most frequently resulted in injuries to the face, specifically parts of the jaw, cheekbones, nose, and bones around the eyes. According to their hypothesis, bones should have evolved to be sturdier at these stress points—and that is exactly what they found in the facial features of early humans. “The bones that break most frequently when modern humans fight are the ones that increase in size and robustness in the faces of the early hominins four to five million years ago,” says Carrier.

When advancing a new idea about human evolution, it is best to be prepared for a bloody fight. This lesson was recently learned by biologist David Carrier and emergency room physician Michael Morgan, both of the University of Utah, when they published a paper theorizing that the human face looks the way it does, in part, because it evolved to take a punch. Carrier and Morgan examined emergency room statistics from Western societies and found that fights between untrained combatants most frequently resulted in injuries to the face, specifically parts of the jaw, cheekbones, nose, and bones around the eyes. According to their hypothesis, bones should have evolved to be sturdier at these stress points—and that is exactly what they found in the facial features of early humans. “The bones that break most frequently when modern humans fight are the ones that increase in size and robustness in the faces of the early hominins four to five million years ago,” says Carrier.

Yet this idea seems to have received almost universal scorn from paleoanthropologists, resulting in testy exchanges between the authors and critics in online forums. Owen Lovejoy of Kent State University believes that Carrier and Morgan’s hypothesis is an example of “adaptationism,” which he defines as assigning an evolutionary purpose to a particular trait when no such relationship exists. Lovejoy believes that the human face is an example of a “spandrel,” an architectural term repurposed by evolutionary biologists Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin to mean a physical trait that evolves as a byproduct of other traits. For example, Lovejoy says, the shape of the human face is a result of brain size and the bones and muscles necessary for chewing. The ability to resist a punch, Lovejoy continues, is incidental, as it wouldn’t provide a significant evolutionary advantage.

Carrier counters that male hominins who were better able to resist punches would have been more successful in the competition for mates, which can be violent in many primate species. And where other primates use long, sharp canine teeth as primary weapons, hominins would have pummeled each other with their hands. Lovejoy reserves some of his strongest criticism for this idea.

He points out that over several million years, hominins have evolved smaller canine teeth, which are used to signal aggression in modern apes, suggesting that early human females didn’t prize aggression in their mates. “Females were choosing males with smaller canines, which means they were choosing nonaggressive males,” he says. The reason that hominins spread across the world while other primates did not may have been cooperation between males, he adds.

He points out that over several million years, hominins have evolved smaller canine teeth, which are used to signal aggression in modern apes, suggesting that early human females didn’t prize aggression in their mates. “Females were choosing males with smaller canines, which means they were choosing nonaggressive males,” he says. The reason that hominins spread across the world while other primates did not may have been cooperation between males, he adds.

Both Carrier and Lovejoy are experts in evolutionary science—but not in the “sweet science.” Boxing trainer Hector Rock has mentored 21 world champions at Gleason’s Gym in Brooklyn, New York, in a career spanning four decades. His experience undercuts Carrier and Morgan’s theory as well. He emphasizes that throwing a punch and taking a punch involve the whole body, not just the hands and skull. “The body is the best part to punch,” he says, “under the ribs.” Carrier plans to continue researching how violence may have shaped the human body, but it remains to be seen whether paleoanthropologists have dealt a body blow to his ideas about the evolution of the human face.

Off the Grid

By MALIN GRUNBERG BANYASZ

Monday, August 11, 2014

Just 20 minutes by car from the center of Florence, Italy, the town of Fiesole boasts great restaurants, shops, and incredible views of Florence’s iconic skyline from the hilltop monastery of San Francesco. Fiesole is rich in Roman ruins and provides significant insight into the development of the area’s older Etruscan civilization. The Etruscan town likely dates back to the ninth and eighth centuries B.C., and the settlement reached the height of its prosperity between the fifth and second centuries b.c. Archaeologist Marco de Marco of the Civic Archaeology Museum of Fiesole says that Vipsl, as ancient Fiesole was known, owed its fortunes to its strategic position on the roads linking central-southern Etruria to the Po Valley. This period came to an end with the Roman conquest of Fiesole in 90 B.C., which resulted in the destruction of most Etruscan buildings there.

Just 20 minutes by car from the center of Florence, Italy, the town of Fiesole boasts great restaurants, shops, and incredible views of Florence’s iconic skyline from the hilltop monastery of San Francesco. Fiesole is rich in Roman ruins and provides significant insight into the development of the area’s older Etruscan civilization. The Etruscan town likely dates back to the ninth and eighth centuries B.C., and the settlement reached the height of its prosperity between the fifth and second centuries b.c. Archaeologist Marco de Marco of the Civic Archaeology Museum of Fiesole says that Vipsl, as ancient Fiesole was known, owed its fortunes to its strategic position on the roads linking central-southern Etruria to the Po Valley. This period came to an end with the Roman conquest of Fiesole in 90 B.C., which resulted in the destruction of most Etruscan buildings there.

The site

Today, there are three main Etruscan features still visible. An Etruscan temple was found on the north side of the town, and archaeologists have been able to reconstruct its original layout from surviving pieces of its walls. City walls dating to the fourth century b.c. are also visible, and extend for approximately a mile and a half around the city. Outside these walls are the remains of Etruscan tombs known as the Via Bargillino tombs. Six in all, they date to the third century b.c., and consist of large stone slab walls and roofs. The Civic Archaeology Museum holds the tombs’ contents, including pottery, weapons, and tools. The Romans left their own mark on Fiesole after a brief period of abandonment following the conquest. In addition to reorganizing and rebuilding the original Etruscan temple, the Romans constructed both a theater and baths, as they did in many towns and settlements. The semicircular theater is one of the best preserved in Tuscany, and includes parts of the original seating (cavea), exit tunnels (vomitoria), and entrances.

While you’re there

While you’re there

The Civic Archaeology Museum of Fiesole documents the ancient history of the area, and includes more than 150 ancient Greek and Etruscan ceramic pieces. Nearby is a museum that covers a more recent period, the Bandini Museum, with spectacular Florentine paintings from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries a.d. Every Tuscan trip is a feast for all the senses, so be sure to try one of Fiesole’s ristorantes, trattorias, osterias, or pasticcerias.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Your Face: Punching Bag or Spandrel?

Off the Grid

Sounds of the Age of Aquarius

Conquest and Clamshells

They're Just Like Us

Modern-Day Ruin

World's Oldest Pants

Off With Their Heads

Alone, but Closely Watched

Saving the Golden House

The Dovedale Hoard

An Ancient Andean Homecoming

Dawn of a Disease

The Case of the Missing Incisors

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement