From the Trenches

The Rabbit Farms of Teotihuacán

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, October 17, 2016

At its peak between the first and fifth centuries A.D., the ancient Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacán accommodated as many as 100,000 people, which made it the largest urban center in the New World. However, archaeologists have sometimes questioned how the city was able to sustain such a sizeable population. Large settlements in other parts of the world usually relied on the domestication of large four-legged mammals such as cattle, sheep, and goats, but these animals were mostly unavailable to the Teotihuacános. A recent study determined that the city’s inhabitants systematically bred leporids—especially cottontails and jackrabbits—for food, fur, and other products that played a crucial role in the city’s food supply and economy. New examination of material from an apartment complex that was excavated several years ago shows that the structure was undoubtedly used for breeding and butchering rabbits. Isotope analysis of the abundant leporid remains indicates that the diet of these animals consisted of human-cultivated crops such as maize or agave, rather than wild plants. “The evidence for leporid management or breeding is important,” says study coleader Andrew Somerville, “because it demonstrates that although New World peoples did not have the fortune of having as many naturally available mammals for domestication as did Old World peoples, they still engaged in intensive relationships with the animals that were there.”

At its peak between the first and fifth centuries A.D., the ancient Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacán accommodated as many as 100,000 people, which made it the largest urban center in the New World. However, archaeologists have sometimes questioned how the city was able to sustain such a sizeable population. Large settlements in other parts of the world usually relied on the domestication of large four-legged mammals such as cattle, sheep, and goats, but these animals were mostly unavailable to the Teotihuacános. A recent study determined that the city’s inhabitants systematically bred leporids—especially cottontails and jackrabbits—for food, fur, and other products that played a crucial role in the city’s food supply and economy. New examination of material from an apartment complex that was excavated several years ago shows that the structure was undoubtedly used for breeding and butchering rabbits. Isotope analysis of the abundant leporid remains indicates that the diet of these animals consisted of human-cultivated crops such as maize or agave, rather than wild plants. “The evidence for leporid management or breeding is important,” says study coleader Andrew Somerville, “because it demonstrates that although New World peoples did not have the fortune of having as many naturally available mammals for domestication as did Old World peoples, they still engaged in intensive relationships with the animals that were there.”

Codex Subtext

By ZACH ZORICH

Monday, October 17, 2016

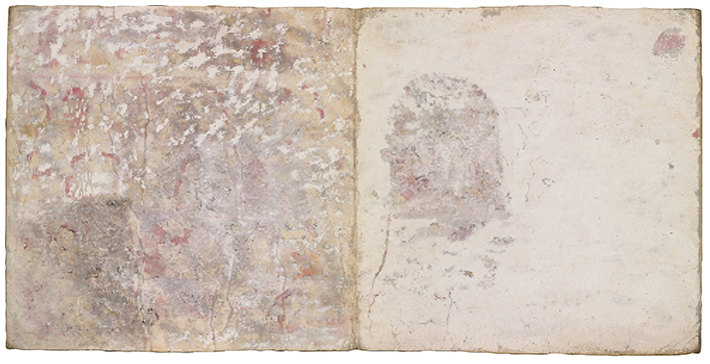

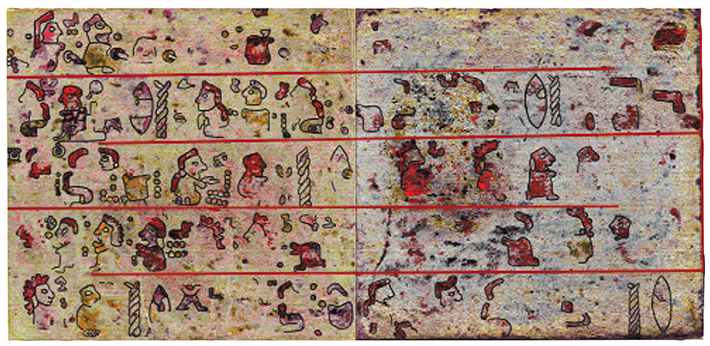

In the mid-1500s, a family of the Mixtec people in Oaxaca, Mexico, recorded their historic deeds in a book now known as the Selden Codex. But books were scarce at the time, so they took an old text, covered it with white gesso, and then painted their new narrative on top. Now researchers in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom have been able to use a technique called hyperspectral imaging to see parts of the older text without damaging the newer one. The images are not sharp enough to read or date the glyphs, but several identifiable figures have emerged, including a line of spear-carrying men possibly marching off to war.

In the mid-1500s, a family of the Mixtec people in Oaxaca, Mexico, recorded their historic deeds in a book now known as the Selden Codex. But books were scarce at the time, so they took an old text, covered it with white gesso, and then painted their new narrative on top. Now researchers in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom have been able to use a technique called hyperspectral imaging to see parts of the older text without damaging the newer one. The images are not sharp enough to read or date the glyphs, but several identifiable figures have emerged, including a line of spear-carrying men possibly marching off to war.

Piltdown’s Lone Forger

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Monday, October 17, 2016

You see before you, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, the coldest of cases, an archaeological fraud perpetrated more than 100 years ago, concerning the evolution of humankind, the scientific process, and personal ambition. It centers on Piltdown Man, paleoanthropology’s greatest whodunit.

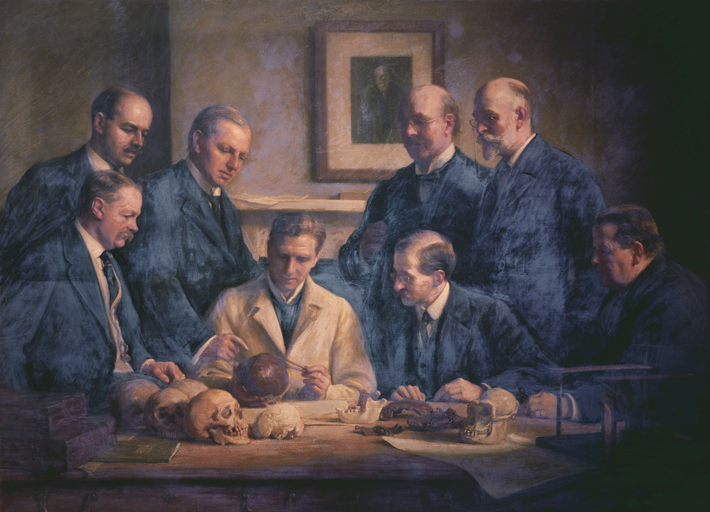

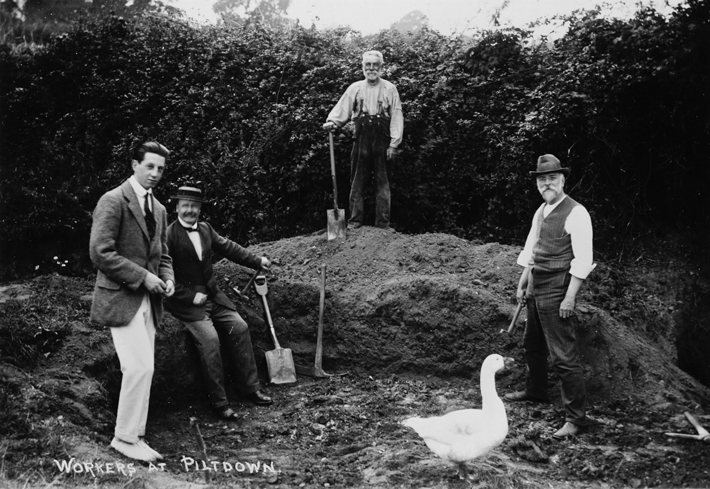

In February 1912, amateur fossil collector Charles Dawson wrote to Arthur Smith Woodward, distinguished Keeper of Geology at the British Museum of Natural History (now just the Natural History Museum), to tell him of a new find, “a thick portion of a human(?) skull.” The previous decades had seen the identification of Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis, and scientists and antiquarians were on the hunt for more—specifically human ancestors with apelike features and bigger, humanlike brains. Two years of excavation at the site of Dawson’s find, Piltdown, Sussex, yielded a simian jawbone with two molars, a canine tooth, parts of a humanlike skull, stone tools, and mammal fossils. Surely the find, named Eanthropus dawsonii (“Dawson’s dawn man”), would be Dawson’s long-coveted ticket into the Royal Society. “People wanted to believe it,” says Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum, who recalls seeing the Piltdown finds on display as a child in the 1950s. “Britain was ready for Piltdown Man.” Dawson died in 1916, but not before he wrote to Woodward of another find, at a site known as Piltdown II, of a tooth and more animal fossils, which Dawson’s wife turned over to the museum.

Doubts dogged Piltdown Man, primarily because the bones didn’t appear to fit with later finds in Africa and Asia. In 1953, Kenneth Oakley, a scientist at the museum, confirmed suspicions and exposed Piltdown Man as a fraud. The jawbone was probably from an orangutan and the skull from a modern human, he found, and they had been manipulated and stained. There have been a number of suspects over the years, in varying conspiratorial combinations. Suspicion usually falls on four: Dawson, Woodward, Teilhard de Chardin (a Jesuit priest who uncovered the canine tooth), and Martin Hinton (a museum volunteer later found to have, among his effects, stained and modified bones). Now the testimony of a multidisciplinary group of scientists who revisited the Piltdown finds with the latest in spectroscopic, radiographic, and genetic technology has placed the spotlight on a single culprit. Their work shows that the Piltdown I and II finds carry the same modus operandi of staining and modification, and that the tooth from Piltdown II likely came from the jawbone from Piltdown I. “The science showed us these hominin specimens are all connected,” says Isabelle De Groote, a paleoanthropologist from Liverpool John Moores University. “They carry the signature of a single forger.” There is only one person associated with the finds at Piltdown II, one man with means, motive, and opportunity to commit the infamous hoax: Charles Dawson. “The tie-up of Piltdown I and II means that it is more than circumstantial,” Stringer says. “I think we can show with a very high degree of certainty that he possessed the orangutan jawbone that created the fakes at both sites. It’s got to be him.”

Doubts dogged Piltdown Man, primarily because the bones didn’t appear to fit with later finds in Africa and Asia. In 1953, Kenneth Oakley, a scientist at the museum, confirmed suspicions and exposed Piltdown Man as a fraud. The jawbone was probably from an orangutan and the skull from a modern human, he found, and they had been manipulated and stained. There have been a number of suspects over the years, in varying conspiratorial combinations. Suspicion usually falls on four: Dawson, Woodward, Teilhard de Chardin (a Jesuit priest who uncovered the canine tooth), and Martin Hinton (a museum volunteer later found to have, among his effects, stained and modified bones). Now the testimony of a multidisciplinary group of scientists who revisited the Piltdown finds with the latest in spectroscopic, radiographic, and genetic technology has placed the spotlight on a single culprit. Their work shows that the Piltdown I and II finds carry the same modus operandi of staining and modification, and that the tooth from Piltdown II likely came from the jawbone from Piltdown I. “The science showed us these hominin specimens are all connected,” says Isabelle De Groote, a paleoanthropologist from Liverpool John Moores University. “They carry the signature of a single forger.” There is only one person associated with the finds at Piltdown II, one man with means, motive, and opportunity to commit the infamous hoax: Charles Dawson. “The tie-up of Piltdown I and II means that it is more than circumstantial,” Stringer says. “I think we can show with a very high degree of certainty that he possessed the orangutan jawbone that created the fakes at both sites. It’s got to be him.”

Dawson was an experienced fossil collector who wrote or coauthored more than 50 scientific publications. He knew precisely what would excite the scientific world and how to obtain bone samples. He was also not reserved in his ambition, having written to Woodward in 1909, “I have been waiting for the big ‘find’ which never seems to come along.” Says Stringer, “Dawson got tired of waiting and decided to help things along.” He also had a history of faking discoveries, including inscribed Roman bricks. These new finds appear to acquit Woodward of fraud, but not of a surfeit of naïveté and a lack of scientific scrutiny. With his work on fossil fish long having been overshadowed by his connection to the fraud, he leaves a lesson for us: Healthy science relies on healthy skepticism.

Off the Grid

By MALIN GRUNBERG BANYASZ

Monday, October 17, 2016

The Gallo-Roman site at present-day Saint-Romain-en-Gal in Rhône, France, was discovered in 1967 when the construction of a high school revealed remains of Vienne, a city known in antiquity as Vienna. It was the capital of the Allobroges, a Gallic tribe, and became a Roman colony in 47 B.C. under the rule of Julius Caesar. Ultimately, Vienna was one of the most important and prosperous towns in Roman Gaul due to its location on the Rhône River. Vienna occupied both sides of the river, with the residential and commercial district on the east, and the political and religious center on the west. The site was excavated annually between 1981 and 2012, when funding dried up. M’hammed Behel, director and conservator at the Gallo-Roman Museum there says it is one of the biggest Roman sites in the country.

The Gallo-Roman site at present-day Saint-Romain-en-Gal in Rhône, France, was discovered in 1967 when the construction of a high school revealed remains of Vienne, a city known in antiquity as Vienna. It was the capital of the Allobroges, a Gallic tribe, and became a Roman colony in 47 B.C. under the rule of Julius Caesar. Ultimately, Vienna was one of the most important and prosperous towns in Roman Gaul due to its location on the Rhône River. Vienna occupied both sides of the river, with the residential and commercial district on the east, and the political and religious center on the west. The site was excavated annually between 1981 and 2012, when funding dried up. M’hammed Behel, director and conservator at the Gallo-Roman Museum there says it is one of the biggest Roman sites in the country.

The site

The 17-acre archaeological site and museum, on the east bank, reveal Vienne’s ancient vitality. Archaeologists have uncovered a craftsmen’s district that features the significant ruins of a mill for fulling, a cleansing step in textile processing. In Roman times, fulling was conducted by slaves, who worked the cloth while ankle-deep in tubs of human urine—a resource so central to the business that it was taxed. Other parts of the site include homes, a commercial area with market halls and warehouses, and the wrestlers’ baths, which contain marble toilets and remarkable frescoes. Exhibits re-create daily life in Roman Gaul, in the form of reconstructions, models, and living history displays. A number of beautiful mosaics—just a fraction of the 250 or so that have been discovered at the site, such as the olive-colored Punishment of Lycurgus and the famous Mosaic of the Ocean Gods—can also be seen. Some of the last finds on the site before excavation halted are a bone pin depicting a woman with an intricate hairstyle and a mausoleum from what was probably Vienna’s first church, dating to around A.D. 450.

While you’re there

While you’re there

The region’s reputation for fine wine extends back to the time of the Allobroges tribe, having been praised by no less than Plutarch and Pliny the Elder. The Vitis Vienna vineyard itself, which dates to the Roman era, was virtually lost to insect infestation before being resurrected in the 1990s, and is now back in production. The mountainous area is also well known for its cheeses, fresh produce, and hearty alpine fare, including chicken liver cake and marmite dauphinoise, a rich broth of veal, beef, pork, and chicken.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Piltdown’s Lone Forger

Off the Grid

Codex Subtext

The Rabbit Farms of Teotihuacán

Murder on the Mountain?

Breaking Cahokia’s Glass Ceiling

Evolve and Catch Fire

Coast over Corridor

Ötzi’s Sartorial Splendor

And They’re Off!

The Blood of the King

China’s Legendary Flood

Shifting Sands

Man Meets Dog, Both Meet Death

World Roundup

Maya victory monument, Neanderthal cannibals, Paleolithic smorgasbord, King Tut’s meteor dagger, and Melanesian tattooing

Artifact

A Cambridge don’s magic shoe

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement