Exploring the beliefs of complex cultures that flourished before the advent of writing challenges archaeologists to imagine how the buildings and artifacts those people left behind express long-vanished belief systems. On the Moche River, six miles inland from the arid northern coast of Peru, loom structures that were central to a people who left behind abundant evidence of their worldview. These buildings, the 15-story adobe-brick Pyramids of the Sun and the Moon, are among the largest built by the Moche, who thrived in northern Peru from about A.D. 200 to 800. Moche artisans produced a rich array of murals, pottery, and other artifacts depicting humans engaged in ceremonies and interacting with mythic creatures. Thanks to these vivid depictions and the lavish burials of priests and nobles, archaeologists can reconstruct how the Moche may have conducted rituals at major sites such as the Pyramids of the Sun and the Moon. But what of the people who lived in smaller settlements far from the major Moche centers? What religious traditions did they follow and what beliefs did they rely on to make sense of the world around them?

In an effort to answer these questions, University of Florida archaeologist Gabriel Prieto has spent years excavating ancient fishing villages north of where the Moche River flows into the Pacific Ocean. In the summer of 2019, he and his team excavated a stone-and-mudbrick platform on a bluff overlooking the Pacific coast at a site known as Pampa la Cruz. Such platforms, which served as temples, were often built by ancient Peruvians, including the Moche, to be used by priests and other important members of the community as stages on which to perform religious rites. Prieto soon discovered that this particular platform, rising a modest six feet high, was decorated with a typical Moche painting that depicts three warriors leading two naked captives. It also concealed evidence of a unique ritual event. Beneath the platform, Prieto unearthed the burials of more than a dozen deep-sea creatures, including nine sharks. The skeletons of two sunfish and two yellowfin tuna, uncommon species on the Peruvian coast, were also identified, as well as two Kogia whales, which are some of the rarest toothed whales in the world. All the animals seemed to have been purposely buried by the people of Pampa la Cruz, who constructed the platform sometime between A.D. 500 and 750. “We were very surprised,” says Prieto. “Perhaps there were offerings of sea animals elsewhere in South America, but we haven’t found them yet.”

The only comparable discovery in the New World was made more than 2,000 miles north, in Mexico City, where the Mexicas, or Aztecs, buried marine species as well as land animals in and around the ritual site of Templo Mayor. “The Aztecs were later than the Moche,” says Harvard University archaeologist Jeffrey Quilter, who visited Pampa la Cruz when the burials were being unearthed. “But both examples reflect the widely shared appreciation by indigenous Americans of animals as important, powerful creatures.” He notes that different animals were sometimes believed to be masters of different planes of reality, including the underworld, which was often imagined as an aquatic realm. “The Pampa la Cruz case is interesting because the animals are oceanic,” says Quilter. “So it seems that the temple had a special role as an intercessor or expression of the forces of the deep.”

Prieto believes that the burials beneath the platform are also an expression of a ceremonial tradition that flourished in the small fishing settlements of the northern Peruvian coast for thousands of years. There, the extremely cold waters of the Humboldt Current create the conditions for a rich, diverse fishery that, even today, is one of the world’s most bountiful. Evidence unearthed by Prieto at Pampa la Cruz and elsewhere shows that rituals based on deep-sea fishing were vital to the people who plied the waters off this stretch of coastline. They were so crucial, Prieto thinks, that they were eventually incorporated into the belief system of the greater Moche world, and help explain how this religious and political system spread throughout northern Peru.

Prieto grew up close to Pampa la Cruz, in the modern-day community of Huanchaco, a coastal resort town about six miles north of Trujillo, Peru’s third-largest city. Huanchaco is home to the last fishing community in South America that relies on traditional techniques that hark back to pre-Columbian times. These fishermen still use watercraft made of reeds that differ little from those used hundreds, even thousands, of years ago. “I grew up knowing these fishermen,” says Prieto, who was drawn to study the lives of the ancient residents of small seaside villages. “I was interested in looking at history from the bottom up. I wanted to explore how common people lived.”

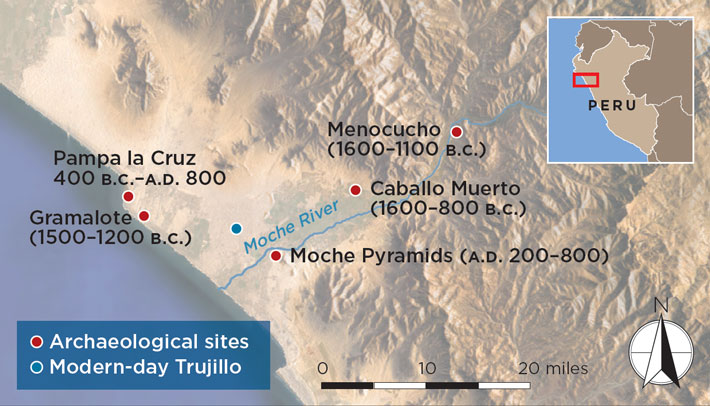

In 2010, Prieto began digging at Gramalote, a prehistoric fishing village with an ancient population of some 300 people that dates to between 1500 and 1200 B.C. Gramalote is just a mile and a half south of Pampa la Cruz, and was occupied at the same time as Menocucho and Caballo Muerto, two larger sites in the nearby Moche River Valley, where hundreds of people lived amid monumental pyramids decorated with murals and adorned with columns. Ceremonial events that drew people from the entire Moche Valley were held at these sites. Previously, archaeologists had proposed that Gramalote was a peripheral community where people focused on providing food, mainly shellfish, to the inhabitants of Menocucho and Caballo Muerto.

Prieto’s excavations soon showed there was much more to life in Gramalote than gathering shellfish. He and his team discovered that the villagers practiced a range of crafts, including basketry and bone carving, and processed large amounts of red pigment. Prieto also collected more than 21,000 fish and 12,000 sea mammal bones, suggesting that deep-sea fishing was just as important as collecting shellfish. Most surprisingly, 16,000 of the fish bones Prieto unearthed were shark vertebras. Then, as now, sharks are not easy prey for humans, but hunting these predators appeared to be one of the main occupations of the people of Gramalote and one of their major sources of meat. These dangerous animals were also symbolically important. Some of the shark vertabras had been polished and drilled as if for use in necklaces, and whole sharks had been placed as offerings under some of the Gramalote dwellings. In a number of burials, Prieto discovered caches of shark teeth, which may have accompanied particularly skilled shark hunters to the afterlife. In once such burial, Prieto also found a reed model of a boat not substantially different from the ones used by the fishermen of Huanchaco today.

The people of Gramalote also seemed perfectly capable of worshipping on their own, without having to make the journey to Menocucho or Caballo Muerto. Prieto unearthed the remains of a small temple complex in Gramalote that bore no resemblance to the grander ritual compounds in the nearby valley. The villagers probably did supply their inland neighbors with food, but they also lived in a self-sufficient community with its own traditions. Prieto notes that when the Spaniards reached the area in the sixteenth century, they found that people in fishing communities spoke a different language from those living just a few miles inland. Perhaps such independence had its roots in an ancient sense of community, centered in part around feats of deep-sea fishing.

Gramalote was abandoned around 1200 B.C., after which archaeologists have an almost 1,000-year gap in their knowledge of the area. Prieto thinks the settlement was moved to a site where Huanchaco’s colonial-era church now stands, making excavation impossible. By 400 B.C., however, a community of some 1,000 people is thought to have been living at Pampa la Cruz. Prieto’s excavations there have revealed that these people did not eat nearly as much shark meat as their ancestors in Gramalote had, but that fishing for sharks still seemed to be symbolically important.

Prieto found that the burial of one high-status man at Pampa la Cruz contained six metal fishhooks, including the largest example ever unearthed in Peru. These hooks are so big that they would only have been used to hunt large fish such as sharks. The grave also contained two cobblestones once wrapped in cotton strings that were likely fishing lines, as well as two flat bone tools that resemble implements still used today by fishermen in Huanchaco to repair nets. This high-status man, whom Prieto dubbed the “fisher chief,” was buried with all the equipment necessary to hunt sharks. But Prieto unearthed almost no shark remains at Pampa la Cruz, where people seem to have consumed mainly small to medium-size fish and shellfish. He concluded that the fisher chief probably had a ceremonial right or ritual responsibility to catch sharks, rather than an obligation to provide shark meat to the community. As an analogy, Prieto points to some indigenous groups in the Amazon whose chiefs must still hunt jaguars, that ecosystem’s top predator, in order to show they are fit to rule. Perhaps, reasons Prieto, the fishing community of Pampa la Cruz retained a memory that their ancestors in Gramalote had been brave shark hunters, and sought leaders who could hunt and kill the ocean’s most dangerous predator.

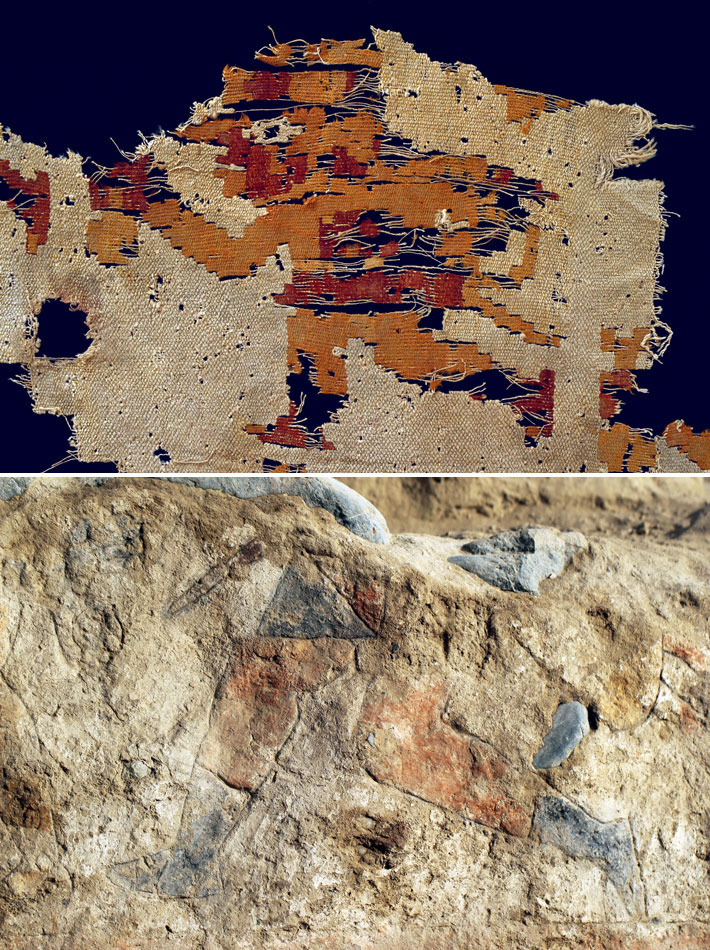

Between A.D. 500 and 550, Pampa la Cruz became part of the Moche world. The main village was demolished and moved 100 yards closer to the ocean. The people of Pampa la Cruz began to be buried with Moche pottery and other artifacts, such as textiles, depicting humans rendered in the Moche style. Prieto found that the storage areas of houses dating to this period were significantly smaller than those in the dwellings that preceded them. Perhaps the villagers were now compelled to supply food to people living some distance away. “It’s possible that once they were part of the Moche world, they had to exchange or barter most of their food at the urban center around the pyramids,” says Prieto. The process of becoming part of the Moche world was a complex one, and, notes Prieto, probably not entirely peaceful. Many human burials his team has unearthed at Pampa la Cruz dating to this period show evidence of violent trauma.

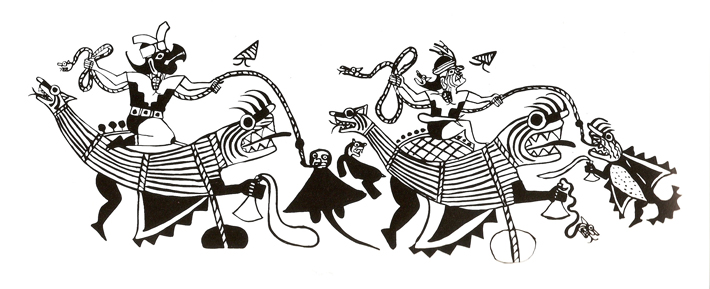

Prieto was convinced that even as the people of Pampa la Cruz fell under the influence of the Moche belief system, deep-sea fishing likely retained its important symbolic role. He was particularly interested in the fact that a common motif on Moche pottery features extravagantly costumed fishermen hunting large sea beasts from reed boats. The animals are sometimes identifiable as sharks or other deep-sea fish, but they are also depicted as chimeras, fantastic creatures that combine features in improbable and frequently bizarre combinations, such as beasts with shark jaws and human limbs. Often the boats themselves seem to be alive, and are portrayed aiding the fishermen in hunting down marine prey. In these depictions, the reed boats piloted by the mythic fishermen resemble the ones used in Huanchaco today.

As he studied these images, Prieto concluded that the people responsible for the spread of the Moche belief system incorporated the symbolism of deep-sea hunting that was so important to the people of small fishing communities such as Pampa la Cruz into their own religion. Perhaps, thought Prieto, these already-ancient beliefs tied to hunting sharks and deep-sea chimeras were included in the Moche ritual system to bolster the appeal of the new ideology to the people of the coast. Thus, the shark-hunting traditions of the Gramalote villagers may have lived on in Moche art, and perhaps even in Moche rituals themselves. “It was clear for me the Moche took this tradition and included it as part of their religious discourse,” says Prieto. “It was one way to legitimize incorporating the fishing villages into their territory.”

Prieto’s theory received dramatic support when he unearthed the burials of the sharks and other deep-sea creatures beneath Pampa la Cruz’s Moche-era platform. Whether it was local people or Moche priests who were responsible for these burials, the people who interred the animals honored ancient rites associated with deep-sea fishing. The fish and whales were even arranged in such a way that they all appeared to be swimming east, as if migrating inland from the waters of the Pacific toward the Moche Valley. Whoever managed to hunt the animals had to have been highly skilled. Similarly, the people who placed the fish and whales below the platform also clearly had intimate knowledge of their behavior. “We don’t know for certain who buried the sea creatures,” says Prieto. “But the fact that they were included in the construction of such an important building is probably the result of a negotiation among higher-ups such as Moche priests and local leaders who had their own tradition that went back to the days of Gramalote.”

The Pampa la Cruz burial ground will contribute to archaeologists’ understanding of the ideology and rituals of the Moche world. “Previous generations of scholars envisioned the Moche spreading their ideology through warfare,” says Denver Museum of Nature & Science archaeologist Michele Koons. “There was this vision of the Moche conquering river valley after river valley and bringing their religion with them. But that’s changing.” New excavations in northern Peru are showing that the Moche world, which was once thought of as unified, was actually much more diverse. It now seems that Moche traditions were not spread strictly through violent coercion as had been thought, but also through a complex series of encounters between the Moche and local people who had their own belief systems. These beliefs weren’t extinguished, but instead found new expressions within the Moche tradition. “This isn’t a story about conquest,” says Koons. “It’s about adaptation.”

The Moche world came to an end sometime around A.D. 800, after which the village of Pampa la Cruz was abandoned. People belonging to the later Chimu culture used the site as a cemetery, where they interred hundreds of ritually sacrificed children (“Peruvian Mass Sacrifice”), but it’s possible the beliefs associated with the fisher chiefs didn’t die out completely. Today, the traditional fishermen of Huanchaco avidly follow Prieto’s excavations. After learning about the discovery of a cemetery that included oceanic creatures, they reminded him that, in their grandparents’ time, fishermen would always offer the biggest fish in their catch to God. They would do this as an act of thanks for the abundance of the ocean’s bounty, perhaps an echo of the beliefs that led the people of Pampa la Cruz to bury sharks beneath their temple.

Slideshow: Surprising Finds Beneath a Peruvian Temple

The excavation of a ritual platform at the ancient village of Pampa la Cruz on Peru’s northern coast has offered University of Florida archaeologist Gabriel Prieto a unique glimpse of a belief system that may have roots in cultural practices that began around 1500 B.C. Dating to between A.D. 500 and 750, the platform was constructed during an era when the fishing community of Pampa la Cruz became part of the world of the Moche, who flourished in northern Peru from A.D. 200 to 800. The unprecedented discovery of marine animal burials beneath the platform suggest that the people who constructed it incorporated long-standing local beliefs into the design of this Moche religious site. All the following images from the Pampa la Cruz excavation are courtesy of Gabriel Prieto.