Digs & Discoveries

Reindeer Training

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, August 10, 2020

Unusual artifacts fashioned from antlers found at a site in northwest Siberia suggest that reindeer were domesticated far earlier than once thought. When archaeologists first discovered the 2,000-year-old L-shaped objects at Ust’-Polui in the Yamal region, they were perplexed. The barbed prongs included in some of them were particularly puzzling. It was not until the team consulted with members of nearby Nenets communities that they finally learned the items’ function.

Unusual artifacts fashioned from antlers found at a site in northwest Siberia suggest that reindeer were domesticated far earlier than once thought. When archaeologists first discovered the 2,000-year-old L-shaped objects at Ust’-Polui in the Yamal region, they were perplexed. The barbed prongs included in some of them were particularly puzzling. It was not until the team consulted with members of nearby Nenets communities that they finally learned the items’ function.

According to these modern-day reindeer herders, the ancient items were probably part of headgear harnesses used to train young reindeer to pull sleds. Since the barbs would have been painful, the animals would have quickly learned not to resist. “When I first saw these artifacts I had no idea how they might have been used,” says University of Alberta anthropologist Robert Losey. “I had never seen reindeer-harnessing equipment outside of a museum, so these objects were completely puzzling. Without the Nenets’ shared knowledge, we would really still be clueless about them.”

It was previously thought that reindeer domestication in northern Europe began around the eleventh century A.D., but the newly discovered equipment pushes that date back by at least 1,000 years.

Dark Earth in the Amazon

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Monday, August 10, 2020

Beginning around 6,000 years ago, people living in the Amazon created fertile plots of land on which to grow food. In a new study, an interdisciplinary team of researchers has found that the work of these early farmers had a marked effect on the rain forest’s biodiversity that remains detectable today. The researchers determined that vegetation grows more readily, and edible plants are richer and more varied, in eastern and southern Amazonia on patches of land called Amazonian Dark Earths (ADEs) than in the surrounding landscape. These are patches ranging in size from less than five to more than 1,200 acres, whose soil ancient people enriched with refuse, including food waste, charcoal, and ceramics. This enabled them to intensively cultivate the land despite its nutrient-poor soil. Archaeologist José Iriarte of the University of Exeter explains that ADEs started without a purpose, with the accumulation of organic refuse. “This only happens when many people dump a lot of trash for a long time,” he says.

Beginning around 6,000 years ago, people living in the Amazon created fertile plots of land on which to grow food. In a new study, an interdisciplinary team of researchers has found that the work of these early farmers had a marked effect on the rain forest’s biodiversity that remains detectable today. The researchers determined that vegetation grows more readily, and edible plants are richer and more varied, in eastern and southern Amazonia on patches of land called Amazonian Dark Earths (ADEs) than in the surrounding landscape. These are patches ranging in size from less than five to more than 1,200 acres, whose soil ancient people enriched with refuse, including food waste, charcoal, and ceramics. This enabled them to intensively cultivate the land despite its nutrient-poor soil. Archaeologist José Iriarte of the University of Exeter explains that ADEs started without a purpose, with the accumulation of organic refuse. “This only happens when many people dump a lot of trash for a long time,” he says.

Widespread intentional ADE development began around 2,500 years ago with the arrival of the Pocó and later Santarém cultures, centered in what is now northern Brazil. The Santarém inhabited nearly 9,000 square miles along the Amazon’s river channels and deeper into the jungle. They also used controlled fires and limited land clearance on enriched field plots in surrounding forests to grow maize, manioc, squash, sweet potatoes, and possibly even stands of fruit trees. Says Iriarte, “In the last 2,000 years, Amazonian people modified their environment at a scale not seen before.”

Missing Mosaics

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Monday, August 10, 2020

In 1922, partial excavation of a Roman villa in Negrar di Valpolicella near Verona revealed several rooms containing brightly colored wall paintings and mosaic floors. Although photographs of the dig survive, the rooms were reburied and their precise location was eventually forgotten. Nearly a century later, archaeologists led by Gianni de Zuccato of the Superintendency of Fine Arts and Landscape of Verona, Rovigo, and Vicenza have rediscovered the geometric-patterned mosaics in a vineyard. The mosaics’ similarity to others found in the region has prompted scholars to date them to anywhere from the mid-third to the fifth century A.D. However, de Zuccato and his team have found clear evidence that parts of the villa were occupied even after the end of the Roman Empire. “We found a fireplace made of a pair of large recycled tiles that destroyed the mosaic below,” de Zuccato says. “These later inhabitants even buried their dead inside the villa.”

In 1922, partial excavation of a Roman villa in Negrar di Valpolicella near Verona revealed several rooms containing brightly colored wall paintings and mosaic floors. Although photographs of the dig survive, the rooms were reburied and their precise location was eventually forgotten. Nearly a century later, archaeologists led by Gianni de Zuccato of the Superintendency of Fine Arts and Landscape of Verona, Rovigo, and Vicenza have rediscovered the geometric-patterned mosaics in a vineyard. The mosaics’ similarity to others found in the region has prompted scholars to date them to anywhere from the mid-third to the fifth century A.D. However, de Zuccato and his team have found clear evidence that parts of the villa were occupied even after the end of the Roman Empire. “We found a fireplace made of a pair of large recycled tiles that destroyed the mosaic below,” de Zuccato says. “These later inhabitants even buried their dead inside the villa.”

Stonehenge's New Neighbor

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, August 10, 2020

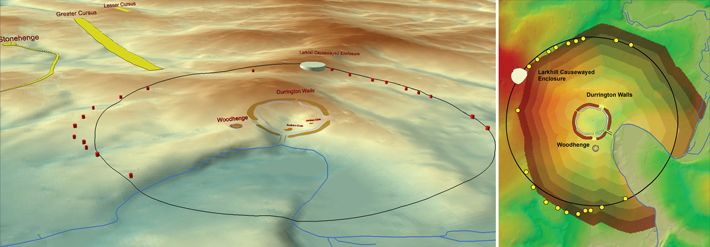

Using remote sensing, archaeologists have identified a series of massive Neolithic pits two miles northeast of Stonehenge that were once part of Britain’s largest sacred prehistoric complex. “Stonehenge has been studied by archaeologists and antiquaries for several hundred years,” says University of Bradford archaeologist Vincent Gaffney. “One might have expected nothing of this scale could be left to find.”

Using remote sensing, archaeologists have identified a series of massive Neolithic pits two miles northeast of Stonehenge that were once part of Britain’s largest sacred prehistoric complex. “Stonehenge has been studied by archaeologists and antiquaries for several hundred years,” says University of Bradford archaeologist Vincent Gaffney. “One might have expected nothing of this scale could be left to find.”

The team identified evidence for 20 huge shafts, each measuring around 33 feet in diameter and 16 feet deep when they were created 4,500 years ago. By plotting the shafts’ locations on a broader map of the region, the researchers realized that they formed a huge circle 1.2 miles in diameter around the site of Durrington Walls. The shafts may have originally demarcated the sacred henge site’s boundary, guiding pilgrims toward the ritual space or warning others not to enter it. “Identifying these pits has added enormously to our understanding of the Stonehenge landscape overall,” says Gaffney. “Durrington Walls was the largest of Britain’s henges, and this discovery adds not just to the size but to the complexity of the life story of that monument.”

Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, August 10, 2020

In the heart of the mountains of southeast Iran’s province of Sistan and Baluchestan, archaeologists have identified a history of continuous occupation dating from prehistory to the present day. The remote region is known for its nearly impassable mountains and arid deserts—as well as its populations of leopards and black bears. Thus far, researchers have identified 12 ancient sites and recovered samples of pottery that will help date them. “In the future we want to work with ethnographers to look at what the similarities are between today’s societies in the region and those of the prehistoric period,” says Hossein Vahedi of Shahrekord University. Of particular note, he says, is the persistence of circular architecture, which first appeared in the prehistoric period and is still used by the region’s seminomadic inhabitants.

In the heart of the mountains of southeast Iran’s province of Sistan and Baluchestan, archaeologists have identified a history of continuous occupation dating from prehistory to the present day. The remote region is known for its nearly impassable mountains and arid deserts—as well as its populations of leopards and black bears. Thus far, researchers have identified 12 ancient sites and recovered samples of pottery that will help date them. “In the future we want to work with ethnographers to look at what the similarities are between today’s societies in the region and those of the prehistoric period,” says Hossein Vahedi of Shahrekord University. Of particular note, he says, is the persistence of circular architecture, which first appeared in the prehistoric period and is still used by the region’s seminomadic inhabitants.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Digs & Discoveries

Siberian Island Enigma

Off the Grid

Closing in on a Pharaoh's Tomb

A Rare Egg

Mouse in the House

Commander's Orders

The Means of Production

Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Missing Mosaics

Stonehenge's New Neighbor

Dark Earth in the Amazon

Reindeer Training

Around the World

A president’s torpedo boat, Cahokia corn farmers, a Viking surprise, and Genghis Khan in winter

Artifact

Reeling in the years

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement