Digs & Discoveries

Off the Grid

By MARLEY BROWN

Thursday, February 11, 2021

For some 13,000 years, Native people in the southern Great Plains obtained flint from an outcrop of dolomite chert that straddles the Texas Panhandle’s Canadian River. Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument, which is named after early twentieth-century rancher Allen “Allie” Bates, features an arresting landscape of arroyos, bluffs, and more than 700 hand-dug quarry pits. The site has been visited and exploited by humans for millennia, but is only known to contain permanent settlement remains dating to the period when the Antelope Creek culture occupied the area. People belonging to this sedentary culture built stone houses, hunted bison, and grew maize between about A.D. 1200 and 1450. “The assumption is that people who lived in the village were the excavators of the quarry pits, given the time and labor involved,” says local archaeologist Paul Katz. In addition to making tools for their own use, the community also produced hand ax–shaped bifaces for trade. These bifaces could then be used to make a variety of tools.

For some 13,000 years, Native people in the southern Great Plains obtained flint from an outcrop of dolomite chert that straddles the Texas Panhandle’s Canadian River. Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument, which is named after early twentieth-century rancher Allen “Allie” Bates, features an arresting landscape of arroyos, bluffs, and more than 700 hand-dug quarry pits. The site has been visited and exploited by humans for millennia, but is only known to contain permanent settlement remains dating to the period when the Antelope Creek culture occupied the area. People belonging to this sedentary culture built stone houses, hunted bison, and grew maize between about A.D. 1200 and 1450. “The assumption is that people who lived in the village were the excavators of the quarry pits, given the time and labor involved,” says local archaeologist Paul Katz. In addition to making tools for their own use, the community also produced hand ax–shaped bifaces for trade. These bifaces could then be used to make a variety of tools.

Alibates flint is known for its distinctive striping and coloring, and archaeologists have identified the site as the source for stone tools dating back to the Clovis culture, between around 13,000 and 11,000 years ago. Some researchers have suggested that Alibates flint was traded or carried beyond the Great Plains and used into the historic period for gunflints. By 1540, when Spanish explorer Francisco Coronado rode through the area, the Antelope Creek people had gone. Texas State University archaeologist Chris Lintz says that upwards of 50 percent of the lithic material found at some contemporaneous prehistoric sites in southern Kansas comes from Alibates. “It’s possible that the end of Antelope Creek played out like The Grapes of Wrath,” he says. “After a devastating drought, these communities may have gradually integrated with their trading partners to the north, possibly Caddoan-speaking ancestors of today’s Wichita, Pawnee, and Kitsai.”

THE SITE

THE SITE

The monument contains both the flint outcrop and quarry pits and the Antelope Creek village ruins. Tours of the ruins are only offered on four Saturdays in October, so contact the monument’s visitor center well in advance of traveling. The visitor center provides background on the prehistoric Great Plains and the Antelope Creek culture. A tour of the village includes a look at several house foundations and a visit to a number of petroglyphs, including depictions of turtles, human feet, and a bison. Ranger-led tours of the flint outcrop and quarry pits are usually available seven days a week. Contact the park for availability and bring your own vehicle, which you will use to follow rangers down a paved road between the visitor center and the trailhead.

WHILE YOU’RE THERE

Katz and Lintz recommend immersing yourself in the history of the region at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon before heading out to Alibates. Just over an hour’s drive south from Alibates is Palo Duro Canyon, the United States’ second-largest canyon. Hike through stunning panoramas of orange and pink hues and set up camp for the night under the stars.

Tyrrhenian Traders

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Thursday, February 11, 2021

A small site on the rocky island of Tavolara off the coast of Sardinia may reveal a robust trading relationship between two Iron Age cultures. In the ninth century B.C., the Nuragic people of the main island of Sardinia exchanged ceramic and metal artifacts with the Villanovans, early Etruscans who inhabited central Italy. Although brooches and other Villanovan metal objects have been unearthed occasionally on Sardinia, evidence of exchange between the cultures has come primarily from Nuragic artifacts found in the tombs of high-status Villanovans in northern Etruria. As a result, scholars think that the Nuragic people and Villanovans mostly interacted on the mainland.

A small site on the rocky island of Tavolara off the coast of Sardinia may reveal a robust trading relationship between two Iron Age cultures. In the ninth century B.C., the Nuragic people of the main island of Sardinia exchanged ceramic and metal artifacts with the Villanovans, early Etruscans who inhabited central Italy. Although brooches and other Villanovan metal objects have been unearthed occasionally on Sardinia, evidence of exchange between the cultures has come primarily from Nuragic artifacts found in the tombs of high-status Villanovans in northern Etruria. As a result, scholars think that the Nuragic people and Villanovans mostly interacted on the mainland.

On a Tavolara beach, however, a team led by Italian archaeologist Paola Mancini recently unearthed the first Villanovan ceramics ever found on Sardinia. Because the researchers have identified no traces of residences there, they believe the site functioned as a kind of trading post. Archaeologist Silvia Amicone of the University of Tübingen carried out scientific analysis of reddish coarseware jars from the site. Her results indicate that the utilitarian vessels originated from different production centers in northern and southern Etruria. According to the researchers, their findings confirm that the Villanovans crossed the Tyrrhenian Sea to visit Sardinia.

More Vesuvius Victims

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Thursday, February 11, 2021

In the ruins of a luxurious villa overlooking the Bay of Naples at Civita Giuliana, half a mile northwest of Pompeii, archaeologists recently discovered the remains of two men killed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79. The researchers were able to create highly accurate casts of the men’s bodies, including details of the clothing they wore while trying to flee the surge of superheated gas and ash that raced through their home on the eruption’s second morning. One man, who showed signs of having performed repetitive physical labor, was between 18 and 25 years of age and wore a short wool tunic. The other was between 30 and 40 and wore both a wool tunic and a mantle, perhaps indicating that he was of higher status.

In the ruins of a luxurious villa overlooking the Bay of Naples at Civita Giuliana, half a mile northwest of Pompeii, archaeologists recently discovered the remains of two men killed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79. The researchers were able to create highly accurate casts of the men’s bodies, including details of the clothing they wore while trying to flee the surge of superheated gas and ash that raced through their home on the eruption’s second morning. One man, who showed signs of having performed repetitive physical labor, was between 18 and 25 years of age and wore a short wool tunic. The other was between 30 and 40 and wore both a wool tunic and a mantle, perhaps indicating that he was of higher status.

Flower Child

By DANIEL WEISS

Thursday, February 11, 2021

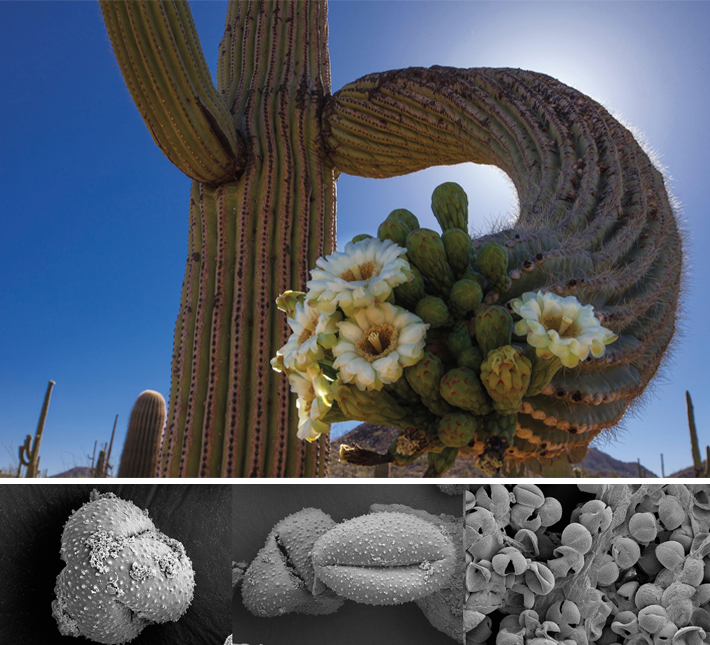

A child belonging to the Hohokam culture who died in southern Arizona’s Sonoran Desert 500 to 1,000 years ago appears to have been fed a special diet in the final weeks of life that included hundreds of saguaro cactus flowers. Partially mummified remains of the child, who died at the age of five or six of unknown causes, were recovered in the early 1940s. Starting in the 1980s, Karl Reinhard, an environmental archaeologist at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, analyzed fossilized excrement, called coprolites, found inside the mummy. He has learned that the child ate saguaro cactus fruit, flour made from ground mesquite pods, and cholla or prickly pear cactus buds, all of which are well-known staples still eaten in the region. Consumption of saguaro flowers, which come from a cactus sacred to the Hohokam, however, was previously undocumented in the area.

A child belonging to the Hohokam culture who died in southern Arizona’s Sonoran Desert 500 to 1,000 years ago appears to have been fed a special diet in the final weeks of life that included hundreds of saguaro cactus flowers. Partially mummified remains of the child, who died at the age of five or six of unknown causes, were recovered in the early 1940s. Starting in the 1980s, Karl Reinhard, an environmental archaeologist at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, analyzed fossilized excrement, called coprolites, found inside the mummy. He has learned that the child ate saguaro cactus fruit, flour made from ground mesquite pods, and cholla or prickly pear cactus buds, all of which are well-known staples still eaten in the region. Consumption of saguaro flowers, which come from a cactus sacred to the Hohokam, however, was previously undocumented in the area.

In the 1990s, the child’s mummy was returned to the Tohono O’odham Nation, who live in the region today, and Reinhard has consulted with the tribal council regarding his study of the coprolites. Recently, a team led by Reinhard reexamined microscopic residues of one of the coprolites using scanning electron microscopy and identified a quantity of saguaro cactus pollen equivalent to more than 200 flowers. Harvesting these flowers, which grow high up on the cacti amid sharp needles, would have required significant effort—saguaro cacti often reach 40 feet in height. This suggests to Reinhard that the child was accorded compassionate palliative treatment as he or she neared death. “We have a lot of thought going into what to feed this child,” he says.

Lady Killer

By MARLEY BROWN

Thursday, February 11, 2021

When researchers discovered the burial of an individual interred with stone implements and projectile points at Wilamaya Patjxa, a site in southern Peru occupied by hunter-gatherers some 9,000 years ago, they had little doubt as to the role the deceased had played while alive. “It was clear that the tools buried with this individual reflected a hunter’s toolkit,” says archaeologist Randy Haas of the University of California, Davis. Initially, the team assumed the hunter was a high-status male, but osteological analysis and a new technique that examines differences between X and Y chromosome versions of a particular gene in tooth enamel determined that the remains actually belonged to a young woman. According to Haas, the division between men as hunters and women as foragers often described in ethnographies of hunter-gatherer groups may not have been so rigid in Paleolithic societies. “When there was a lot of big game, both men and women would have focused their effort on these resources, which gave you a lot of bang for your buck,” he says. When these animals became less plentiful and diets became more diverse, Haas explains, communal hunts involving all capable adults may have gradually given way to gender-based specialization.

When researchers discovered the burial of an individual interred with stone implements and projectile points at Wilamaya Patjxa, a site in southern Peru occupied by hunter-gatherers some 9,000 years ago, they had little doubt as to the role the deceased had played while alive. “It was clear that the tools buried with this individual reflected a hunter’s toolkit,” says archaeologist Randy Haas of the University of California, Davis. Initially, the team assumed the hunter was a high-status male, but osteological analysis and a new technique that examines differences between X and Y chromosome versions of a particular gene in tooth enamel determined that the remains actually belonged to a young woman. According to Haas, the division between men as hunters and women as foragers often described in ethnographies of hunter-gatherer groups may not have been so rigid in Paleolithic societies. “When there was a lot of big game, both men and women would have focused their effort on these resources, which gave you a lot of bang for your buck,” he says. When these animals became less plentiful and diets became more diverse, Haas explains, communal hunts involving all capable adults may have gradually given way to gender-based specialization.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

The Amazing True Story of Nathan Harrison

The Visigoths' Imperial Ambitions

Letter from Chihuahua

Digs & Discoveries

An Enduring Design

The Mummies Return

A Dutiful Roman Soldier

In Full Plume

Joust Like a King

Temple of Heaven

Lady Killer

More Vesuvius Victims

Flower Child

Tyrrhenian Traders

Off the Grid

Around the World

Neanderthal burial practices, Mexican marigold, Levantine bananas, and defending a Phoenician colony

Artifact

Ancient athletic accoutrements

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement