Digs & Discoveries

A Barrel of Bronze Age Monkeys

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

Scholars have longed believed that a Bronze Age Aegean painting of a troop of monkeys depicts stylized exotic primates cavorting about a rocky landscape. The fresco adorns a room in a two-story complex at the second-millennium B.C. settlement of Akrotiri on the Greek island of Thera. No monkeys are native to the region, and the depictions were thought to have been made by painters following Egyptian stylistic conventions, which often rendered animal species as abstract types. Now, a team led by University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Marie Nicole Pareja that includes primatologists and a taxonomic illustrator has concluded that the Akrotiri monkeys are, in fact, accurate depictions of langur monkeys, whose natural range is the Indus River Valley, some 4,000 miles away.

Scholars have longed believed that a Bronze Age Aegean painting of a troop of monkeys depicts stylized exotic primates cavorting about a rocky landscape. The fresco adorns a room in a two-story complex at the second-millennium B.C. settlement of Akrotiri on the Greek island of Thera. No monkeys are native to the region, and the depictions were thought to have been made by painters following Egyptian stylistic conventions, which often rendered animal species as abstract types. Now, a team led by University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Marie Nicole Pareja that includes primatologists and a taxonomic illustrator has concluded that the Akrotiri monkeys are, in fact, accurate depictions of langur monkeys, whose natural range is the Indus River Valley, some 4,000 miles away.

The researchers observed that the Akrotiri monkeys have S- or C-shaped tails, just as langurs do. Pareja believes this key detail shows that the artists who created the fresco must have seen the primates with their own eyes. “We think they had direct contact with the langurs,” says Pareja. “Textual sources suggest Mesopotamians imported critters from the Indus Valley, so it’s possible the painters encountered the langurs there, or elsewhere in the Near East.”

Bicycles and Bayonets

By DANIEL WEISS

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

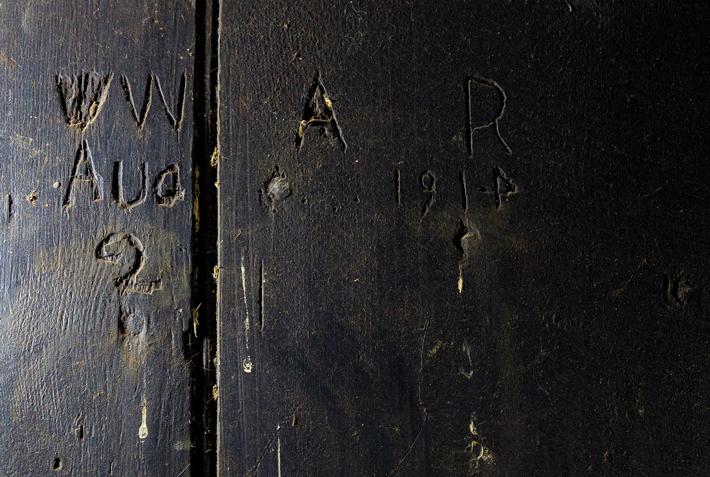

Recently discovered graffiti carved into a stable door at a farm in Lincolnshire during the first decades of the twentieth century mixes bucolic childhood concerns with matters of far greater import. Looming above images of plows, horses, and a bicycle is a stark record of the day Great Britain entered World War I: “WAR AUG 4 1914.” Below this date sits a question mark. “I wonder if this is someone asking, ‘When’s it going to end?’” says Ian Marshman, historic environment officer at the Lincolnshire County Council. The artists also signed their work with two sets of initials—WB and JL—and an abbreviated name, J. Leusley.

Recently discovered graffiti carved into a stable door at a farm in Lincolnshire during the first decades of the twentieth century mixes bucolic childhood concerns with matters of far greater import. Looming above images of plows, horses, and a bicycle is a stark record of the day Great Britain entered World War I: “WAR AUG 4 1914.” Below this date sits a question mark. “I wonder if this is someone asking, ‘When’s it going to end?’” says Ian Marshman, historic environment officer at the Lincolnshire County Council. The artists also signed their work with two sets of initials—WB and JL—and an abbreviated name, J. Leusley.

Marshman and his colleagues used census information to determine that WB was William Bristow, part of the family that owned the farm, and JL was John Leusley, a son of the owner of a nearby pub, The Axe & Handsaw. It’s likely the initials and other images were carved into the door years before the beginning of the war, when Bristow would have been around 22 and Leusley around 29. Bristow appears to have remained on the farm during the war, while Leusley was injured in France and received a partial pension, suggesting he could still work, but not at his skilled prewar job as a steam engine driver.

Marshman and his colleagues used census information to determine that WB was William Bristow, part of the family that owned the farm, and JL was John Leusley, a son of the owner of a nearby pub, The Axe & Handsaw. It’s likely the initials and other images were carved into the door years before the beginning of the war, when Bristow would have been around 22 and Leusley around 29. Bristow appears to have remained on the farm during the war, while Leusley was injured in France and received a partial pension, suggesting he could still work, but not at his skilled prewar job as a steam engine driver.

Ancient Academia

By DANIEL WEISS

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

In some respects, the life of a Mesopotamian scholar in the seventh century B.C. was not so very different from that of a modern academic. While the former might be responsible for reporting on celestial phenomena and whether they augur well for the king’s reign, and the latter might be searching for evidence of a new subatomic particle to better understand the origins of the universe, in either case, one’s reputation among colleagues is paramount.

In some respects, the life of a Mesopotamian scholar in the seventh century B.C. was not so very different from that of a modern academic. While the former might be responsible for reporting on celestial phenomena and whether they augur well for the king’s reign, and the latter might be searching for evidence of a new subatomic particle to better understand the origins of the universe, in either case, one’s reputation among colleagues is paramount.

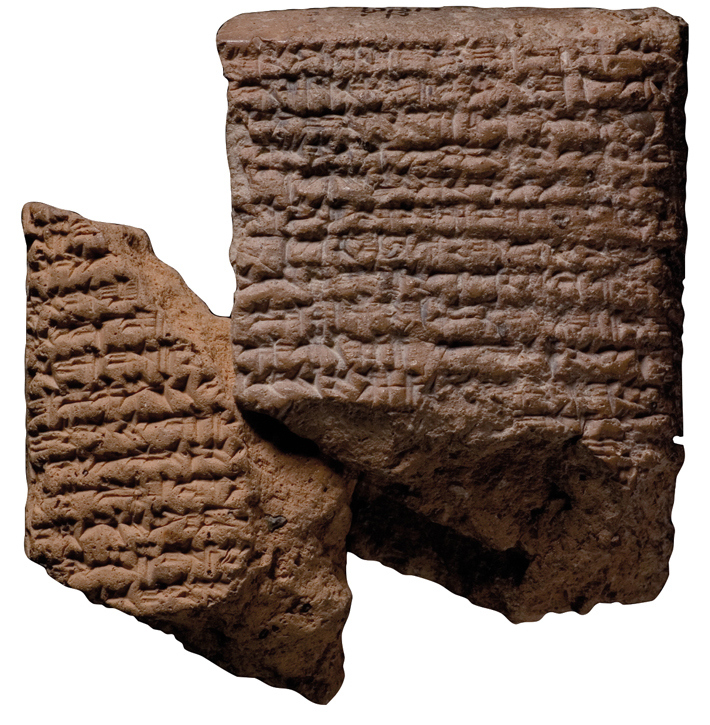

Let’s take, for example, the lot of an unnamed astrologer who was subjected to a vicious onslaught of peer review from some of the Neo-Assyrian Empire’s top minds after claiming to have sighted Venus around 669 B.C. In a letter to the king Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 B.C.), a fellow stargazer named Nabû-ahhe-eriba, who was part of the inner circle of royal scholars, inveighed, “(He who) wrote to the king, my lord, ‘The planet Venus is visible, it is visible (in the month Ad)ar,’ is a vile man, an ignoramus, a cheat!” Slightly more charitable, though still cutting, was a scholar named Balasî, who tutored the crown prince Ashurbanipal (r. 668–627 B.C.). “(T)he man who wrote (thus) to the king, (my lord), is in ignorance,” Balasî informed Esarhaddon. “The ig(noramus)—who is he?…I repeat: He does not understand (the difference) between Mercury and Venus.”

These quotations are excerpts from just two of around 1,000 letters and reports written by scholars to Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal in cuneiform on clay tablets that were discovered during nineteenth-century excavations of the archives of the Assyrian capital, Nineveh, near Mosul in Iraq, including Ashurbanipal’s library. While researchers once viewed the ancient scholars as passive instruments of the king who lacked any independence, Assyriologists including Jennifer Singletary, until recently a researcher at the University of Gottingen, are now exploring how the letters illustrate both adversarial and friendly interactions among the scholars, as well as how scholars took distinctive approaches in their writing. “Assyriologists have tended to overemphasize the influence of the king and underemphasize the individuality of the scholars,” says Singletary. “I have been focusing more on the scholars’ relationships with one another and on how their interactions as colleagues and rivals influenced the writing they produced.”

When they weren’t excoriating fellow scholars they considered incompetent or deceitful, many ancient scholars collaborated with each other, frequently across city lines. This was particularly important when it came to astronomical observations, whose success could depend on the local weather. “Now there are clouds everywhere; we do not know whether the eclipse took place or not,” Bel-ušezib, a Babylonian scholar based in Nineveh, told Esarhaddon. “Let the lord of kings write to Assur and all the cities, to Babylon, to Nippur, to Uruk and Borsippa; maybe they observed it in these cities.”

Having connections to an extensive network of colleagues, particularly if they were widely geographically dispersed, could help a scholar find favor with the king. For instance, when a Babylonian astrologer named Marduk-šapik-zeri, who had fallen out of favor with Esarhaddon, tried to return to the king’s good graces, he cited not just his skill at observing good and bad portents in the sky, but also his connection to “twenty competent scholars worthy of royal desire.” These included a haruspex, or diviner, from Elam, in Iran, several exorcists from Assyria, and various other physicians and chanters.

Having connections to an extensive network of colleagues, particularly if they were widely geographically dispersed, could help a scholar find favor with the king. For instance, when a Babylonian astrologer named Marduk-šapik-zeri, who had fallen out of favor with Esarhaddon, tried to return to the king’s good graces, he cited not just his skill at observing good and bad portents in the sky, but also his connection to “twenty competent scholars worthy of royal desire.” These included a haruspex, or diviner, from Elam, in Iran, several exorcists from Assyria, and various other physicians and chanters.

Singletary points out that both Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal had good reason to encourage communication among scholars throughout the empire. Both kings were younger sons who were elevated to the throne over older brothers, causing intense controversy and strife during their respective reigns. Keeping tabs on omens discovered by a broad range of scholars was, therefore, highly advantageous. In Ashurbanipal’s case, he became king of Assyria while his older brother was named king of Babylon, a lesser yet competing position. “Ashurbanipal collected scholars almost the same way he collected tablets for his library,” says Singletary. “I wonder if his interest in making sure he was engaging with scholars in Babylonia as well as Assyria had to do with getting insider knowledge from his brother’s portion of the kingdom to make sure there weren’t any uprisings there.”

Off the Grid

By MARLEY BROWN

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

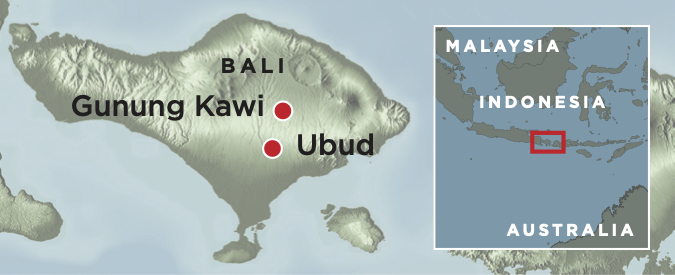

Some 1,000 years ago, stonemasons cut into a basalt escarpment in a river valley outside the modern Balinese village of Tampaksiring. They carved out a nearly 100-foot-wide courtyard backed by a 40-foot-tall vertical wall. Into this wall they carved five shrines, called candis, each almost 30 feet tall and intended to resemble temple facades. Across the small river bisecting the valley, the masons carved another courtyard and four more, slightly smaller, candis. A tenth candi is set apart from the others. The two courtyards and the candis, as well as a number of small artificial caves that may once have been used as prayer or living spaces for monks, make up the site of Gunung Kawi. This is one of many temple complexes built on Java and Bali starting around the first century A.D., when Hinduism and then Buddhism began to come to Indonesia from the Indian subcontinent. The Gunung Kawi complex was likely built to memorialize the Balinese ruler Anak Wungsu, who died around A.D. 1077. The smaller candis are thought to commemorate Wungsu’s children, wives, and concubines. “Multiple queens or children get a monument that’s 95 percent the size of the monument to the king,” says archaeologist John Schoenfelder of the University of Massachusetts Boston, “so they are being categorized as nearly as important.” Schoenfelder suggests that this relative lack of hierarchy emphasizes the fact that the extended royal household was considered a single entity. At Gunung Kawi, the ruler and his kin were venerated alongside patron gods with whom they were reincorporated after death.

Some 1,000 years ago, stonemasons cut into a basalt escarpment in a river valley outside the modern Balinese village of Tampaksiring. They carved out a nearly 100-foot-wide courtyard backed by a 40-foot-tall vertical wall. Into this wall they carved five shrines, called candis, each almost 30 feet tall and intended to resemble temple facades. Across the small river bisecting the valley, the masons carved another courtyard and four more, slightly smaller, candis. A tenth candi is set apart from the others. The two courtyards and the candis, as well as a number of small artificial caves that may once have been used as prayer or living spaces for monks, make up the site of Gunung Kawi. This is one of many temple complexes built on Java and Bali starting around the first century A.D., when Hinduism and then Buddhism began to come to Indonesia from the Indian subcontinent. The Gunung Kawi complex was likely built to memorialize the Balinese ruler Anak Wungsu, who died around A.D. 1077. The smaller candis are thought to commemorate Wungsu’s children, wives, and concubines. “Multiple queens or children get a monument that’s 95 percent the size of the monument to the king,” says archaeologist John Schoenfelder of the University of Massachusetts Boston, “so they are being categorized as nearly as important.” Schoenfelder suggests that this relative lack of hierarchy emphasizes the fact that the extended royal household was considered a single entity. At Gunung Kawi, the ruler and his kin were venerated alongside patron gods with whom they were reincorporated after death.

THE SITE

The entrance to Gunung Kawi is a short walk from the center of Tampaksiring and a half-hour taxi ride from the popular tourist town of Ubud. Beyond a gauntlet of souvenir stalls, a steep set of more than 300 stairs leads down into the valley. The price of admission includes the rental of a sarong and sash, which are customarily worn when visiting temples in Bali. Very little in the way of interpretive display is available at the site, so you may wish to inquire with local tour agencies or at your hotel about hiring a guide.

WHILE YOU'RE THERE

WHILE YOU'RE THERE

Gunung Kawi, as well as nearby Tirta Empul, a water temple just half a mile north that has been visited for centuries by pilgrims seeking ritual purification, is nestled within an ancient landscape of rice terraces and irrigation canals. Between temple visits, sign up for a walking tour along one of the various pathways in the Ubud area to witness firsthand the inextricable connection—both physical and symbolic—between Balinese agriculture and religious life.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Digs & Discoveries

Ancient Academia

Off the Grid

Bicycles and Bayonets

A Barrel of Bronze Age Monkeys

Domestic Harmony

Shock of the Old

Sailing the Viking Seas

Egyptian Coneheads

China's Carp Catchers

Field of Tombs

Bird on a Wire

Tool Time

Protecting the Young

Early Adopters

Around the World

Neolithic chewing gum DNA, the first sled dogs, and swelling the ranks of the Terracotta Army

Artifact

Ahead of the curve

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement