From the Trenches

Henry VIII’s Favorite Palace

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, October 16, 2017

Of all the estates and houses available to King Henry VIII, Greenwich Palace in southeast London was known to be his favorite. The king spent more than 4,000 nights there (that’s almost 11 years in total), and he added a number of structures to it, including an armory staffed by metalsmiths from abroad. The palace was largely razed by the end of the seventeenth century, and little sign of it remains aboveground. Recently, however, two of its rooms were unearthed during construction of a visitor center at the Old Royal Naval College, which sits on the palace’s former grounds. “We knew it was quite likely we might find the odd bit of historical Greenwich,” says William Palin, director of conservation at the Old Royal Naval College, “but nothing quite prepared us for the discoveries that were made.” One of the rooms had lead-glazed tiles, and researchers believe it may have been a part of Henry VIII’s armory. The other featured a number of niches thought to have been used as “bee boles,” where hive baskets were kept warm during the winter months.

The Glass Economy

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, October 16, 2017

Researchers working in southwestern Nigeria have uncovered thousands of glass beads, fragments of crucibles, and other evidence of glass production at the site of Igbo Olokun in the ancient Yoruba city of Ile-Ife. Excavators have discovered examples of a type of soda-lime glass that was likely brought to the area by Islamic traders, as well as a much greater number of locally produced glass beads. According to Abidemi Babalola of Harvard University, who led the research, these beads, which the community valued for rituals, healing, and trade, could have been the product of a unique local glass production formula that turned Ile-Ife into a major manufacturing center between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries. “The geology of Ile-Ife certainly supports glass production, which could have inspired local exploration and experimentation,” Babalola explains. “The question is whether dwindling local production necessitated importation, or contact with imported glass inspired the experimentation.”

Researchers working in southwestern Nigeria have uncovered thousands of glass beads, fragments of crucibles, and other evidence of glass production at the site of Igbo Olokun in the ancient Yoruba city of Ile-Ife. Excavators have discovered examples of a type of soda-lime glass that was likely brought to the area by Islamic traders, as well as a much greater number of locally produced glass beads. According to Abidemi Babalola of Harvard University, who led the research, these beads, which the community valued for rituals, healing, and trade, could have been the product of a unique local glass production formula that turned Ile-Ife into a major manufacturing center between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries. “The geology of Ile-Ife certainly supports glass production, which could have inspired local exploration and experimentation,” Babalola explains. “The question is whether dwindling local production necessitated importation, or contact with imported glass inspired the experimentation.”

Putting on a New Face

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, October 16, 2017

While the streets, houses, and shops of ancient Herculaneum were preserved to a remarkable degree by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79, its vibrant frescoes have suffered a tremendous toll in the years since they were first exposed. By using a new portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) device called Elio, chemist Eleonora Del Federico of the Pratt Institute has been able to see behind the damage to the surface of a painting excavated in the House of the Mosaic Atrium 70 years ago. “Using this device we can see a complex and sophisticated painting technique with details not visible to the naked eye today,” says Del Federico. But it was the “iron map”—XRF shows researchers the elemental composition of artifacts and how the elements are distributed within the object—that Del Federico says “blew her mind.” She says, “The iron map shows not only a beautiful woman, with detail, but also reveals her thoughtful expression and, for me, her humanity. Looking at the iron map, to me, is like looking into this woman’s soul.”

While the streets, houses, and shops of ancient Herculaneum were preserved to a remarkable degree by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79, its vibrant frescoes have suffered a tremendous toll in the years since they were first exposed. By using a new portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) device called Elio, chemist Eleonora Del Federico of the Pratt Institute has been able to see behind the damage to the surface of a painting excavated in the House of the Mosaic Atrium 70 years ago. “Using this device we can see a complex and sophisticated painting technique with details not visible to the naked eye today,” says Del Federico. But it was the “iron map”—XRF shows researchers the elemental composition of artifacts and how the elements are distributed within the object—that Del Federico says “blew her mind.” She says, “The iron map shows not only a beautiful woman, with detail, but also reveals her thoughtful expression and, for me, her humanity. Looking at the iron map, to me, is like looking into this woman’s soul.”

Fit for a Saint

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, October 16, 2017

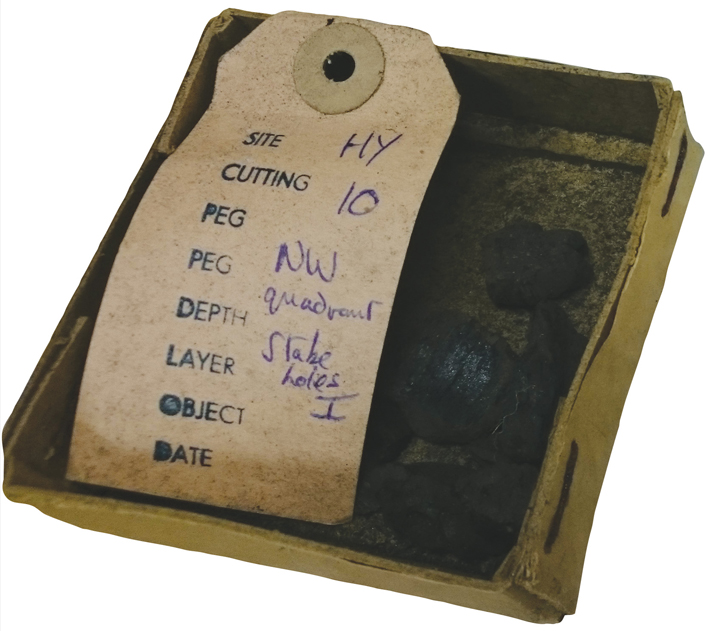

Analysis of charcoal from Scotland’s monastery island of Iona has concluded that a wooden hut often associated with Saint Columba indeed dates to his lifetime in the late sixth century. Columba, an Irish abbot and missionary, was a dominant force in the spread of Christianity throughout Scotland. He founded the monastery on Iona, which stood as a bastion of literacy and scholarship for centuries and attracted legions of pilgrims until Catholic Mass was made illegal during the Reformation in the sixteenth century. Originally uncovered in the 1950s by archaeologists Charles Thomas, Peter Fowler, and Elizabeth Fowler, the charcoal comes from an ash layer of Tórr an Abba, or “Mound of the Abbot,” on the monastery’s grounds. While the three scholars believed they had found evidence of Columba’s cell, which appears to have been turned into a monument not long after his death in 597, they were never able to prove it.

Analysis of charcoal from Scotland’s monastery island of Iona has concluded that a wooden hut often associated with Saint Columba indeed dates to his lifetime in the late sixth century. Columba, an Irish abbot and missionary, was a dominant force in the spread of Christianity throughout Scotland. He founded the monastery on Iona, which stood as a bastion of literacy and scholarship for centuries and attracted legions of pilgrims until Catholic Mass was made illegal during the Reformation in the sixteenth century. Originally uncovered in the 1950s by archaeologists Charles Thomas, Peter Fowler, and Elizabeth Fowler, the charcoal comes from an ash layer of Tórr an Abba, or “Mound of the Abbot,” on the monastery’s grounds. While the three scholars believed they had found evidence of Columba’s cell, which appears to have been turned into a monument not long after his death in 597, they were never able to prove it.

After storing the Iona samples for years in his own garage, Thomas bequeathed them to Historic Environment Scotland, which teamed up with archaeologists from the University of Glasgow to radiocarbon date the material and revisit the site. “What they excavated in the 1950s was a hut that didn’t look like it had many stages, perhaps one or two constructions,” says lead archaeologist Adrián Maldonado. “At some point it burned down and that’s the charcoal we were able to date.” The latest possible date for the charcoal is A.D. 650, making it likely that Columba, and perhaps later abbots too, used the cell.

After storing the Iona samples for years in his own garage, Thomas bequeathed them to Historic Environment Scotland, which teamed up with archaeologists from the University of Glasgow to radiocarbon date the material and revisit the site. “What they excavated in the 1950s was a hut that didn’t look like it had many stages, perhaps one or two constructions,” says lead archaeologist Adrián Maldonado. “At some point it burned down and that’s the charcoal we were able to date.” The latest possible date for the charcoal is A.D. 650, making it likely that Columba, and perhaps later abbots too, used the cell.

Living Evidence

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, October 16, 2017

In recent years, scientists have determined that early humans interbred with other hominin species, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans, by comparing the genomes of present-day humans with DNA taken from hominin fossils. Now, however, evidence of interbreeding has been found based on analysis of human genomes drawn from people currently living around the world. Specifically, researchers have focused on a gene called MUC7, which codes for a protein found in saliva.

A team led by Omer Gokcumen and Stefan Ruhl of the State University of New York at Buffalo studied how MUC7 varied in 2,500 present-day human genomes. To their surprise, it took a dramatically different form in around 5 percent of people from sub-Saharan Africa. The most likely explanation, the researchers concluded, was that some 150,000 to 200,000 years ago, a group of humans in Africa interbred with an unknown hominin species, whose version of MUC7 has been passed down to people living there today.

Although this interbreeding took place before humans left Africa, the mystery hominin’s genes appear not to have been carried by those who left the continent. Based on known rates of genetic mutation, the hominin appears to have diverged from modern humans around one to two million years ago, and the researchers believe it was probably similar to other hominin species of the era, such as Homo erectus, Neanderthals, and Denisovans, in terms of brainpower and technological skill.

As genomic techniques grow more refined, Gokcumen believes we will detect more and more instances in which early humans interbred with other hominin species. “We are seeing that there were multiple humanlike groups that modern humans absorbed rather than replaced,” he says. “We are only seeing them now because we are able to look at entire genomes.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

The Hidden Stories of the York Gospel

Off the Grid

Iconic Discovery

Arctic Ice Maiden

Desert Life

Living Evidence

Putting on a New Face

Fit for a Saint

The Glass Economy

Henry VIII’s Favorite Palace

Itinerant Etruscan Beekeepers

Spain’s Silver Boom

Conspicuous Consumption

Tablet Time

By the Light of the Moon

World Roundup

Viking cod exports, Bronze Age cereal box, Commodore Perry’s Revenge, Easter Island ecology, and Zanzibar’s colonial past

Artifact

A face from the past

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement